A conversation with the emerging artist about his latest projects delving into the real and virtual worlds of Ghana’s queer communities

As far as inspirational discoveries go, one of my most recent happened where most great ones do. On Instagram. A trip to Accra had me trawling through my feed to see a multitude of artistic happenings in the growing cultural pulse point. It was there that I came across a striking monochrome image of a male form abstracted by the lazy haze of an equatorial sunbeam. This was a work by Eric Gyamfi, and the real discovery was that I was a little late to this particular party.

Born in 1990, Gyamfi is an Accra-based photographer and printmaker whose on-going study of Ghanaian social life has been exhibited at Rencontres De Bamako and LagosPhoto and profiled in Aperture, The New York Times and The Huffington Post. He’s also been the recipient of the 2017 Open Society Foundation Grant and invited participant of the 2017 World Press Photo West African Master Class.

His practice is committed to the creation of images in its embodiment of the indomitable questions that circle his medium. From Gyamfi’s studio in Adenta, I touched on some of these questions with the artist. These included perceptions of what a photograph is (in the Instagram age) and his thoughts on what it means to be a viewer of the surrounding world as an individual and also as part of society.

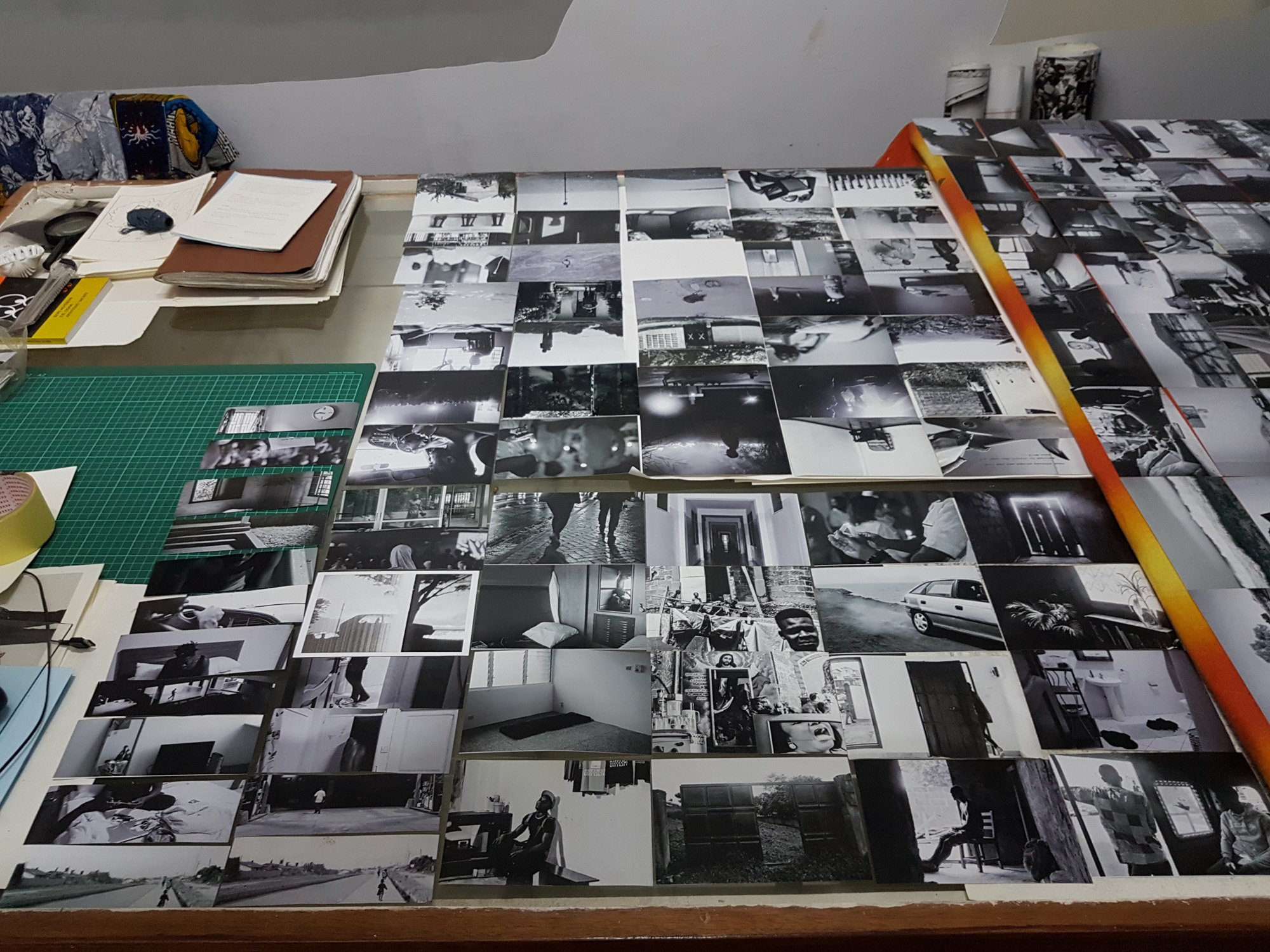

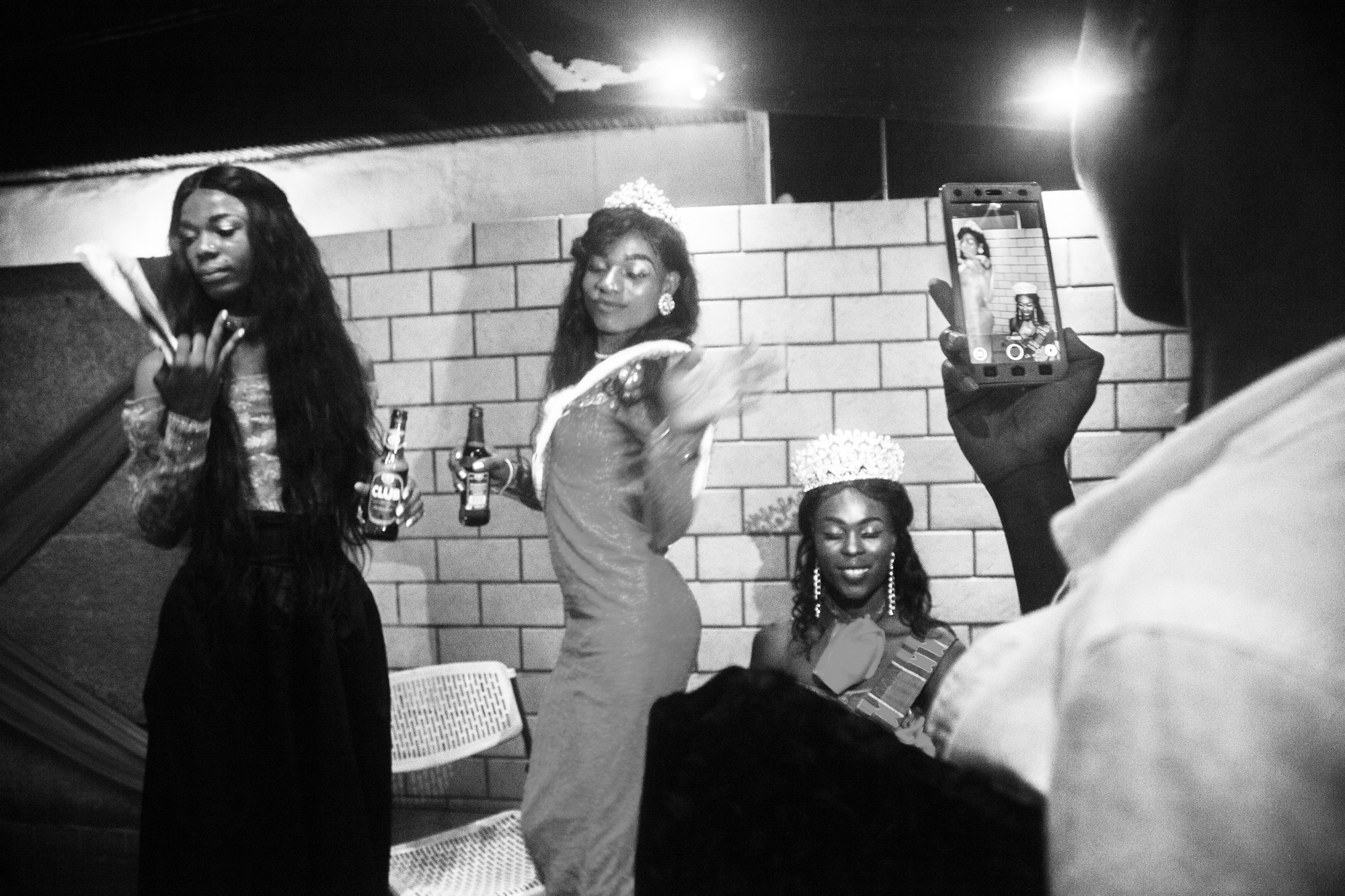

Gyamfi’s most well known and constantly evolving project, Just Like Us, preoccupies itself with the latter question. Surveying queer communities on the periphery of Ghana’s complex social fabric, it was initially received as a documentary series but now incorporates the responses of viewers as photographic, site-specific installations. The most recent, Just Like Us: Constellations at The Goethe Institut in Johannesburg, collapses the beautifully mundane experiences of a community into newly formed images created from handwritten notes and social media captions. With no recourse to simply lose oneself in the conventional pleasures of documentary photography, the significance of collective engagement guides us through the visual experience. Gyamfi is now further evolving his exploration of queer spaces in Ghana with the new body of work, Fixing Shadows.

TO: What are you working on at the moment?

EG: Fixing shadows. It looks at how photography as a tool can be used to disturb or shift some meanings and histories, especially where some erasures and absences (queer absences) lie. It is a 3-part body of work, for now. The second part looks at some of the ways in which queer men present themselves on Grindr, mostly in Ghana. I’m interested in the layers within those forms of presentations and how they have the potential to speak to certain social experiences and to a degree, the politics of a place.

TO: What sort of things has the project highlighted?

EG: Grindr is supposed to be a safe space for men to relate and find other people. It is very interesting how people present themselves on the platform, what kinds of images they use and what statements they make. I have been paying attention and making screenshots as I travel within the country, looking at these self presentations. However, it’s interesting that although [the platform] is supposed to be a safe space, some of these (re)presentations can speak to some the paranoia and the confusion that queer people, even the seemingly free or liberated ones, face here.

TO: What were some of the conflicts you found?

EG: I’ll show you [flipping through a selection of traced images]… That’s Jay Cole, that’s someone’s back, someone’s front with a big iPad, that’s some statue in Amsterdam, a quarter of someone’s face with their eyes closed, someone’s torso… someone’s torso… someone lips… headless… mouth… faceless… cathedral, headless… that’s his face (but he’s white)… Kanye kissing Kanye (a meme).

TO: These are all things you’ve seen?

EG: Yes, I made screenshots and traced from the images. I haven’t gotten to them all.

TO: So, you’re focusing on the fact that people are not willing to show themselves entirely?

EG: I’m interested in what they choose to present. What kind of statements they attach to what they show and how that has the potential to speak to where they are coming from. In this case, I’m trying to look at profiles from here [in Accra] and from other parts of the country that I see.

TO: What’s the main pattern that you’ve seen so far?

EG: I don’t want to be conclusive because it’s also a study for me. If I state that people are not showing their faces because of homophobia, I’ll be reducing everything to a single experience. I’m just as curious as you are. I’ve found that there is a lot of homophobia on Grindr, which is interesting, because it is a space for queer people. Some of the most popular statements are: ‘no pic, no chat’, ‘no fat, femmes’ sometimes ‘no blacks’. There are instances of white people on Grindr [in Ghana] writing ‘no blacks’. There are layers.

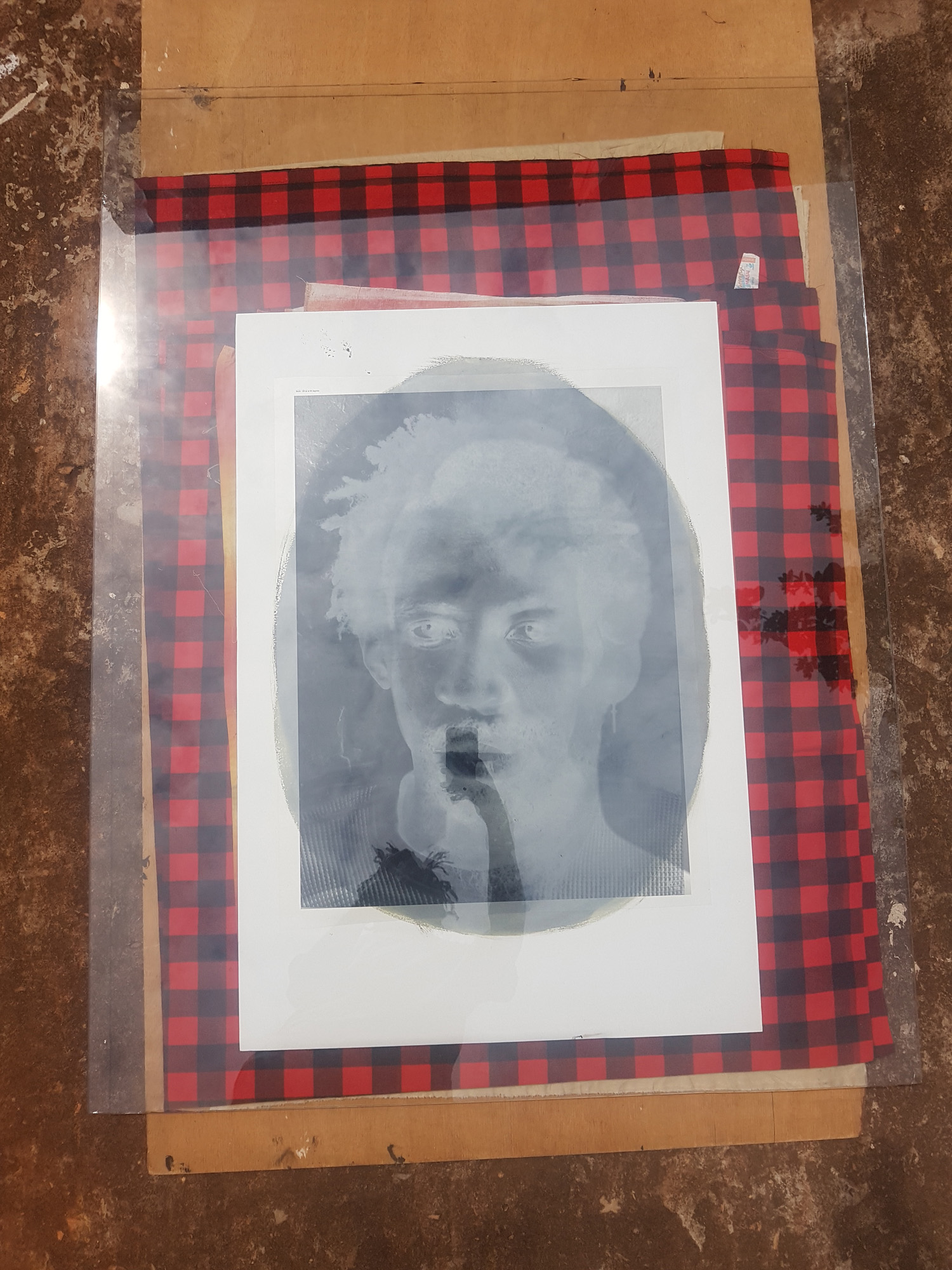

TO: What will your sketches eventually become?

EG: I’ve been experimenting by super imposing images and drawings, re-photographing those and looking at what kind of new images or identities come forward. I find it interesting that with just a phone you can assume a completely different identity and be someone else. I’m not particularly interested in how true that identity is, I’m interested in the ability to split yourself or even layer yourself. Maybe it’s more so about the layering. It almost becomes an additional situation where you’re adding on as opposed to disintegrating. I’m interested in how that affects the psyche. I’m looking at all of this as a way of informing what I’ll do with the images later.

TO: Can you say a bit more about the idea of disintegration?

EG: The ideas in the images dictate the form and process that are used. I feel like disintegration doesn’t work in this case, what people are actuality doing is building layers, like adding on another mask or another skin. Forming more complex ways of being as opposed to splitting and having these little minute experiences. We think of identity as almost desperate forms that we take on. What if they are things that we just build onto what exists already?

TO: What exists already?

EG: [laughs] The body and the ideas it has come to continually imbibe from conception to now. How do you, do we, ever really shed ideas?

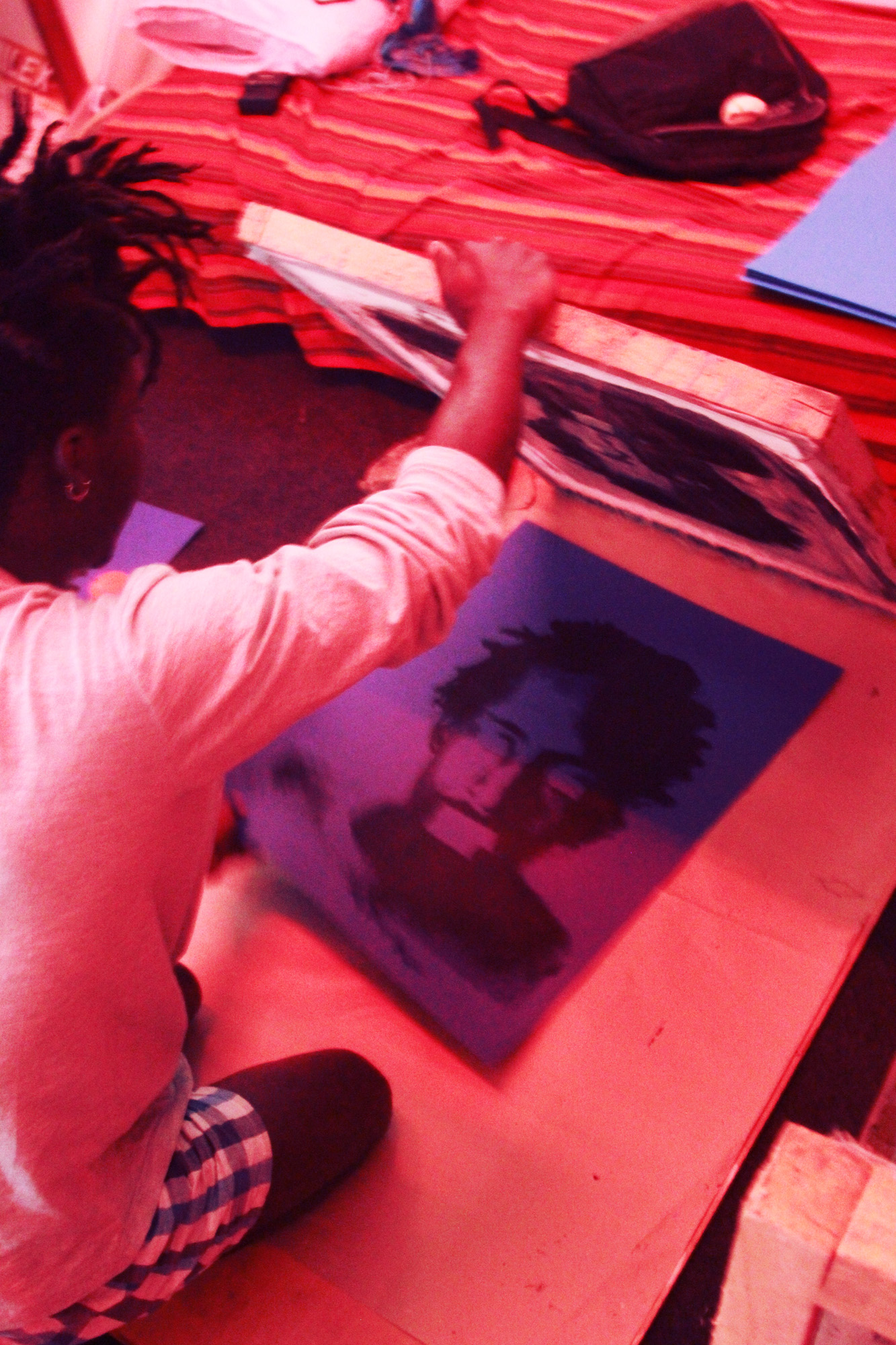

TO: What techniques are you working with?

EG: I’ve been looking at processes that are additional. Initially I looked at the cyanotype process. One, because I love blue, but secondly, the beginnings of the process are also architectural, like a way of making blueprints for buildings. The idea of constructing is interesting because it’s an additional process. You bring this and that and it goes on. I played with that for a while but the results felt flat. The layers get lost. I am thinking something more three dimensional, perhaps recreating my studio light box that has been key to work so far as part of an installation.

TO: How did you choose the title?

EG: I changed it from Social Fabrics to Fixing Shadows after listening to a documentary about William Talbot, and the early process of salt printing. After his successes with the method he’s believed to have said ‘I have found a ways of fixing shadows’. Shadows are interesting formations. The way they change. In some places they are signs of the soul or spirit. But they are also formed from obstructions; something has to block travelling light. The idea of fixing them and what method of fixing we are looking at is an interesting thing to think about.

TO: Fixing Shadows is in conversation with Just Like Us, which began in 2016 and has been exhibited widely. Can you talk a little more about that project?

EG: Just Like Us brought together the stories of people who identify as queer in Ghana and what it means to be such within this geography. My presentation at Nubuke Foundation [in Accra] was the first iteration of Just Like Us. I collected responses from that and folded it back into the second exhibition in Cape Coast during the international day against homophobia. Lots of the people there were in the photographs so it was a way for them to engage with their images. Subsequent presentations of the work have been a collection of photographs and screenshots of social media responses and new images I made when it was published on various virtual media platforms. Looking at the trajectory of the work, where it’s found itself and its point of engagement with the general public, I wanted to bring those responses back to a photographic form.

TO: The presentation of process, like the bulletining and screenshots of comments from social media, feel really important to the work. It’s as if they are as important as the photos.

EG: It’s all project specific, but for me it became important for people to see their own engagement. I get to experience the audiences [responses] to my work but there isn’t the option for viewers to see how a piece of work is considered. This is an interesting concept for me; presenting people’s experiences back to them. You’re not just having your experience now but also a potential experience in addition to the work. I feel it creates a new layer [of engagement] that I don’t think is common.

TO: People often say art holds a mirror up to the world and you are holding a mirror up to the audience. Shifting the mirror is a small move but it speaks to greater continuums. I, a Black British Nigerian Londoner, viewed Just Like Us about Ghanaian culture and that society’s view on queer Ghana within a European cultural institute in South Africa. So many audience structures and points of identification!

EG: There is some irony there, and perhaps this mirror that artists hold up should be held back at them too. I am complicit in a number of ways. I will leave you to write about that. I am curious as to where it fails and where it thrives.

TO: I think what you do with the male form is incredible. Your images give as much pleasure as they do the important work of opening things up. I wanted to talk about the erotic and how that factors into your work.

EG: I hope I presented it in a way that reflects society, but I also feel that I have to find different ways of depicting it.

TO: The queer community in Ghana are at the heart of the projects we are discussing. When I encountered Just Like Us at the Joburg show, it was great to experience the contrast between negative perceptions and a community that is thriving. How did you gain access?

EG: Access is based on participation. I’m not really going out of my way to find that now. Maybe I did in the beginning, to create a connection. Over time it become a matter of people living a similar life or experience and a certain kind of sharing through which comes a certain kind of documentation. But I’m still rethinking what that means now. It’s difficult to feel as though you are spokesperson. I’m asking a lot of questions around that.

TO: What kinds of questions?

EG: I think about what becomes of people in my photographs. On the other hand there is a crazy need to find other modes of documentation. How else can we record, and what are the means? That’s more stimulating and more exciting to me. That is tied to the creation of a language that is more pertinent to our experience here. Documentary photography as a genre has very specific terms of reference from a particular part of the world. What we’ve been doing is building on and extending this tradition. Within my capacity as an artist, how can I take that further or find ways of building on it that speaks to my experience here? I feel that’s where the need for development comes from. I want to be able to speak for people to understand by using the cues from this tradition and other modes of communication where I am presently.

TO: With that said, what excites you now about what you are doing?

EG: I am incredibly excited by the times now because it feels like there is progression and development at every stage. I find that I am sharpening my language and beginning to understand what it means to say what I need to with with tools available to me. I am learning to communicate. It is difficult and exciting.

This interview comes from a partnership between Nataal and People’s Stories Project (PSP) - part of the British Council’s arts programme in sub-Saharan Africa. For more information click here.

Images courtesy of Eric Gyamfi, Moshood Balogun, Kwasi Darko

Visit Eric Gyamfi

Published on 09/08/2018