Nataal’s editorial director contributes to a new book examining Africa’s contemporary art scene and celebrating the opening of Zeitz MOCAA

New book Africa Modern: Creating the Contemporary Art of a Continent surveys the continent’s art landscape and marks the opening of Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town. Independently produced by the charitable KT Wong Foundation in association with Thomas Heatherwick, the architect behind the museum, the book is edited by writer and cultural commentator Ekow Eshun and designed by Wallpaper*.

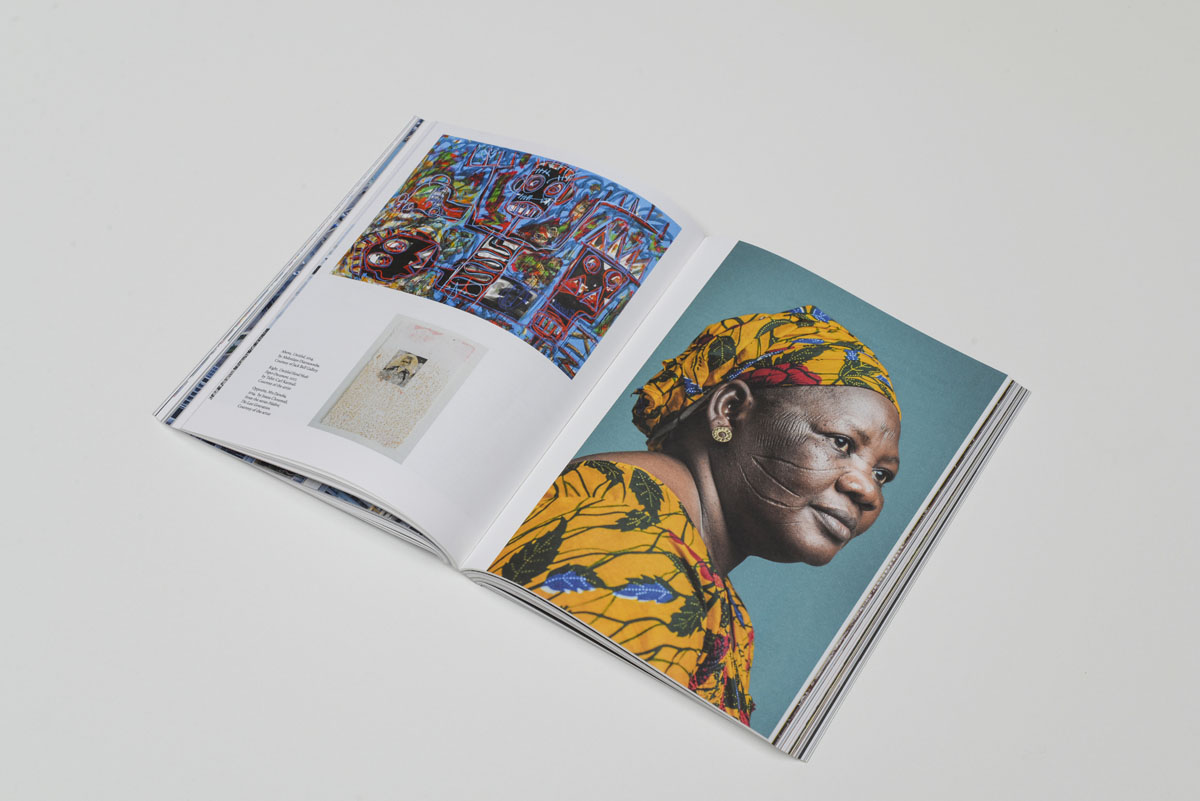

Africa Modern features special visual projects by some of South Africa’s leading lights including Pieter Hugo, Mikhael Subotzky, Mary Sibande, Mohau Modisakeng and Nicholas Hlobo, plus profiles of creators such as William Kentridge, Lukhanyo Mdingi, Southern Guild and Hanneli Rupert. These sit alongside Heatherwick’s personal account of his approach to turning a disused grain silo on the city’s Victoria & Alfred Waterfront into the first major institution on African soil dedicated to thoroughly contemporary African art.

The project started out some years ago with a visit to the dilapidated building with Design Indaba founder and visionary connector Ravi Naidoo, during which Heatherwick recalls that he “crawled around the old structure and trampled across a lot of bird droppings” discovering its unique cellular structure of 116 gigantic vertical tubes. Eventually a grand scheme took shape to build “the missing piece of the jigsaw in the continent’s art world” by philanthropist Jochen Zeitz and curator Mark Coetzee. Needless to say, this was no mean feat. “We could either fight a building made of concrete tubes or find a way to enjoy its tube-iness,” Heatherwick writes. Their breakthrough moment came when they decided to take inspiration from a single grain of corn, its irregular shape now informing the museum’s expertly carved, elegantly curved central atrium from which 80 glorious gallery spaces rise.

“As the designers of the silo’s next incarnation, we have tried to respect the quirks of its sculptural form in order to reveal the previous life of the building as much as possible. Our focus during everything has been to keep and enhance the textural qualities of the original structure,” he writes. “This special public place has been designed to be a dynamic space in which artists will show and create the most extraordinary work, and Capetonians and visitors from all over the world will be able to experience the best contemporary thinking in fine art, sculpture, film, performance and events."

Africa Modern also includes several essays by writers and thinkers including Achille Mbembe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Valerie Kabov, which ruminate on the successes and challenges surrounding African art today. I too have contributed the piece, Tomorrow is now: emerging artists shaping a new Africa.

“I was really keen to get a multiplicity of creative voices involved and, in a small way, paint a portrait of what seems to me to be a particularly dynamic moment in African contemporary art,” Eshun tells Nataal. “The most frustrating aspect of all this, which I reflected on while editing the book and reading some of the essays that came in, is how little support the role of contemporary art gets in Africa. Of course, you always run into a schools and hospitals dilemma in countries that aren’t wealthy - why spend money on art when you have a citizenry that’s struggling to get by? But I’d argue that art and culture are important elements in the fabric of a nation. That’s still a case yet to be made successfully across much of the continent.”

Eshun continues: “One of the consequences of this is that most of the best collections of contemporary African art are held outside the continent in Europe. African nations themselves are missing out on their own cultural wealth. Just even to list a few names - Zanele Muholi, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Njideka Akunyii Crosby, Wangechi Mutu, Serge Attukwei Clottey, Ibrahim Mahama, Edson Chagas Kudzani Chiraui - is to illustrate how rich and how diverse the field of work is that’s emerging from across the continent.”

Africa Modern celebrates these talents and many more, who now both hang on the walls of Zeitz MOCAA’s mighty walls and are being recognised worldwide. But this, in many ways, is only the beginning. “Africa is a place of deeply complex histories and politics and the presentation of art from the continent needs to be able to speak to that density and diversity of stories and identities and pasts,” says Eshun. “And this at a time, when everything is changing in global commerce, people flows and information. That’s both a great basis from which a museum might work from and also a fiendishly complicated one. So there’s a lot of work to do."

Read an exclusive excerpt from Africa Modern: Creating the Contemporary Art of a Continent:

Why Africa needs art museums by Valerie Kabov

It is… unequivocal that art museums in Africa are imperative to the project establishing authoritative and authentic representation of African art both historically and contemporaneously. They are key to genuine ownership of history, legacy, value creation and retention of cultural heritage for future generations, providing access for Africans to the best examples of contemporary art and the value this engenders. Only the locally founded collecting institutions are in a position to at least try to assure democracy and plurality of representation.

It is equally unequivocal that to build up local institutions of the quality and capacity to adequately address these needs is an enormous challenge. While the founding fathers of newly independent African nations, such as Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) and Sékou Touré (Guinea), recognised the importance of cultural nationalism, art could not and has not taken priority above the urgent needs of young nations, such as healthcare, education and infrastructure.

Foreign humanitarian organisations focused on health, social justice and (frequently) diplomatic and political agendas have stepped in to fill the gap left by government funding. This has inevitably meant that the broader social agendas of the funders take precedence over support for economic viability and artistic excellence. Conversely, philanthropic efforts to support African contemporary art have also been largely ex-continental, with the largest collection of contemporary African art having been built up by Italian businessman Jean Pigozzi, who is currently planning to create a museum in Europe to house his collection.

With such a strong international market and institutional collecting effort directed towards the sector, it is more than foreseeable that the vast majority of the most important works by modern and contemporary African artists will be lost to African audiences.

In the Africa Art Market Report 2014, Sindika Dokolo, the Congolese businessman who owns one of the most internationally significant African art collections, said : ‘The real added value of an African collection of art is to expose the African audience to its own contemporary creation. It is a moral and political responsibility and an effort must be made so that our continent is more integrated in the art world circuits. Therefore, I decided early on that my collection would always be available for free for any museum around the world who would be interested in hosting an exhibition. However, I have one demand in that the museum has the obligation to organize the same exhibition in an African country of its choice. We cannot just accept that African art will never be seen in Africa because our continent is still poor and focused on its primordial needs.’

However, while Dokolo’s vision is laudable, it presents only a partial solution. Permanent and permanently accessible public collections are necessary. It is also becoming clear that, as was the case with the first modern art museums in Europe, collaborations and partnerships between local philanthropists and public institutions can be a model for redressing the current imbalances of power that threaten representation and access in African art scenes today.

The new Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town is creating a template for a possible private-public partnership, which will be closely scrutinised by those looking to open art museums elsewhere on the continent and will hopefully provide a catalyst for doing so. Speaking to Conceptual Fine Arts, the museum’s executive director and chief curator, Mark Coetzee, said the MOCAA structure was similar to that of museums such as MoMA or the Guggenheim, which are not-for-profit institutions supported by a large percentage of private funds.

Importantly, there is a consciousness as to why private funding is being sought. Coetzee said : ‘[The Broad or the Rubell Museum] are fully private museums supported by a single family, which run them like private projects...What we wouldn’t like to do is take money from the government, because we are in a very particular moment in our country, with problems about housing, schools and water provision. We also have to be very careful and make sure to position the museum as a public institution, and also as an institution with full freedom of expression.’

Awareness of the role of art museums as an irreplaceable public good, for reasons that exceed the needs of the arts and culture sectors, will be crucial for MOCAA and all that follow. Colonialism and apartheid did more than just bring with them new culture and influences. Colonialists actively worked to destroy art and culture and social and communal structures in Africa, in order to subjugate the continent’s peoples. Today, many of the current development concerns in Africa can be traced back to that destruction of culture and cultural self-esteem.

It is important that MOCAA’s creators are conscious of their part in overcoming a legacy of oppression and exclusion. Coetzee speaks of the need to ‘address a community who have been excluded from cultural participation for 50 years and make them feel that they are welcomed again...We need the communities to feel that this is their museum and we are just the caretakers; it can’t belong to us.’

Art is a space to reclaim and reconstruct the values of the past and build values of the future. Art is also a space for freedom and self-determination. Museums are the environments where art can be accessible to the greatest number with the greatest impact. They are core not just to the art sectors, the social landscape and the broader economy, but also to culture itself.

Africa Modern: Creating the Contemporary Art of a Continent, edited by Ekow Eshun, is published by the KT Wong Foundation

Read our full story on Zeitz MOCAA here.

Published on 01/10/2017