The artist steers us through his major solo at Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna

For years, Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama has dreamt of acquiring and exhibiting British-and German-built locomotives. ‘Zilijifa’, his current exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna – the artist’s first major solo in Austria – realises that ambition with a centrepiece at once monumental and fragile: the stripped shell of a freight train balanced atop columns of enamelled headpans.

The headpan, a ubiquitous vessel in Ghana used by kayayees (head porters) to transport goods, shares the train’s condition: dented, rusting and full of holes. Both are vessels of burden, carriers of raw material and memory. By placing one atop the other, Mahama links industrial infrastructure to the body’s labour, colonial extraction and to everyday survival.

The Ghanaian railway was first laid by the British colonial administration in the 1890s to move minerals, crops and people from the interior to coastal ports. After independence in 1957, the system fell into decline; by the 1980s, rail lines were being torn up and sold for scrap. Since 2022, Mahama has acquired several decommissioned locomotives, preserving what he calls “the scars of history” writ large on these defunct vehicles, along with hundreds of headpans traded directly from workers for new ones.

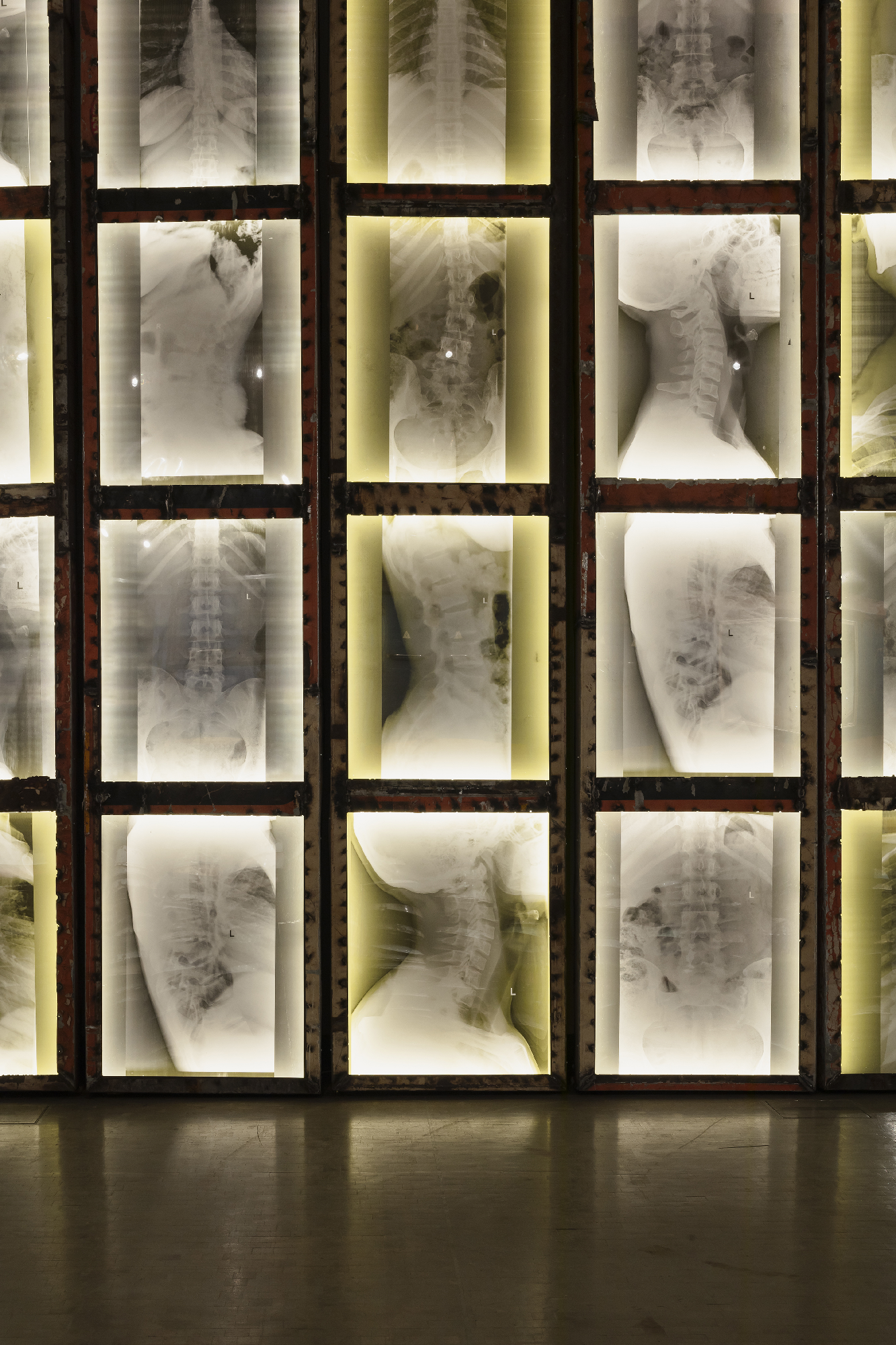

In ‘Go Tell It on the Mountain’ (2025), 125 X-rays of spines deformed by decades of carrying heavy loads are presented in scrap metal lightboxes. The work, a ghostly ledger of pain and exploitation, is forensic yet filled with pathos. On an opposing wall, ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ (2025) features large photographs taken in front of colonial and post-independence trains. Some sitters are kayayees obscured by stacked pans; others face the camera directly, ennobled by the images’ scale. Close-ups capture rusty pans and a stately, half-visible crest.

‘A Dialogue’ (2025), filmed in Accra and Tamale markets, includes excerpts from interviews of people with whom Mahama traded headpans. Their expressions and voices puncture any sense of solemnity that threatens to overshadow the exhibition. Meanwhile, ‘Just Above My Head’ (2025), a five-channel video, documents the exhibition’s making: headpan trades in northern markets, locomotives hauled by road to Red Clay in his hometown of Tamale, and the photo shoot for ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’. It plays on the artist-film convention of revealing studio process, showing the material networks behind the work.

Red Clay is his hybrid space — part studio, part open museum, part educational hub. The footage in ‘Just Above My Head’ captures the welding of frames, the sorting of materials and the welcome of visiting schoolchildren. Established on land bought with proceeds from his first art work sale in 2014, Red Clay serves as a resource for future generations: “If we can inspire kids and demystify the world they live in, then we can think differently about the world they can build,” Mahama says. Today, Red Clay’s sprawling complex houses studios, archives, classrooms, gardens, a greenhouse, and repurposed aircraft. “Every day is open, anyone can come anytime,” he says in a conversation with ‘Zilijifa’ curator and Kunsthalle Wien’s director, Michelle Cotton. Inverting the historic model of African art made for export, Red Clay creates infrastructure for making and sharing work locally. Even wildlife has a place — bats roost in one silo, a living emblem of the cycles of life, death and renewal running through Mahama’s practice.

At Kunsthalle Wien, one walks out of Mahama’s exhibition with its rusted locomotive into the imperial grandeur of MuseumsQuartier’s Baroque façades, the latter a world away from Tamale’s markets, streets and surrounding landscape, where, to quote James Baldwin whose novels give their names to two pieces in this exhibition: “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

“If we can inspire kids and demystify the world they live in, then we can think differently about the world they can build"

Mahama’s early installations used stitched-together jute sacks, their fibres tracing histories of trade, exploitation and reuse. Other projects reanimated discarded tools: ‘Parliament of Ghosts’ (2019) reconstructed Ghana’s parliamentary chamber from decommissioned train seats; ‘Capital Corpse’s (2019–21) mounted obsolete sewing machines onto colonial-era school desks; ‘Garden of Scars’ (2022) cast gravestone rubbings from Ghanaian and Dutch colonial sites in cement mixed with local materials. The silo’s bat colony inspired ‘Lazarus’ (2021), a suspended sculpture of tarpaulin-draped rebar forms suggesting spectral bodies in flight. ‘Purple Hibiscus’ (2024) enveloped the Barbican Centre’s Brutalist façade in precious Ghanaian textiles and robes infused with intergenerational knowledge. Each project treats objects as palimpsests — surfaces inscribed with past lives and open to new meaning.

And with new meaning comes new kinds of value. By bringing sacks, railway parts and other discarded infrastructure into the art economy, Mahama endows them with monetary worth well beyond their former functions, which he then reinvests into all the cultural spaces he has founded in Tamale, where the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art and Nkrumah Volini join the ever-growing Red Clay.

On the day of the ‘Zilijifa’ opening, I ask this celebrated artist what other projects he has in the pipeline. He tells me of an idea he has which involves glass bottles from the 1960s – a far less onerous proposition than transporting an old locomotive from Ghana to Vienna, I assume. Except in typical Mahama fashion there will be 300,000 of these antique vessels, each one imagined as a lamp with a genie inside it from whom three wishes will be granted. “What would you do with 900,000 wishes?” he asks, pausing for a moment to leave the question hanging in the air with all the possibility and potential it invites us as an audience to imagine.

Visit Ibrahim Mahama

Visit Kunsthalle Wien

Words Tendai Mutambu

Published on 25/08/2025