Accra’s Nubuke Foundation marks its reopening with a retrospective of this legendary photographer

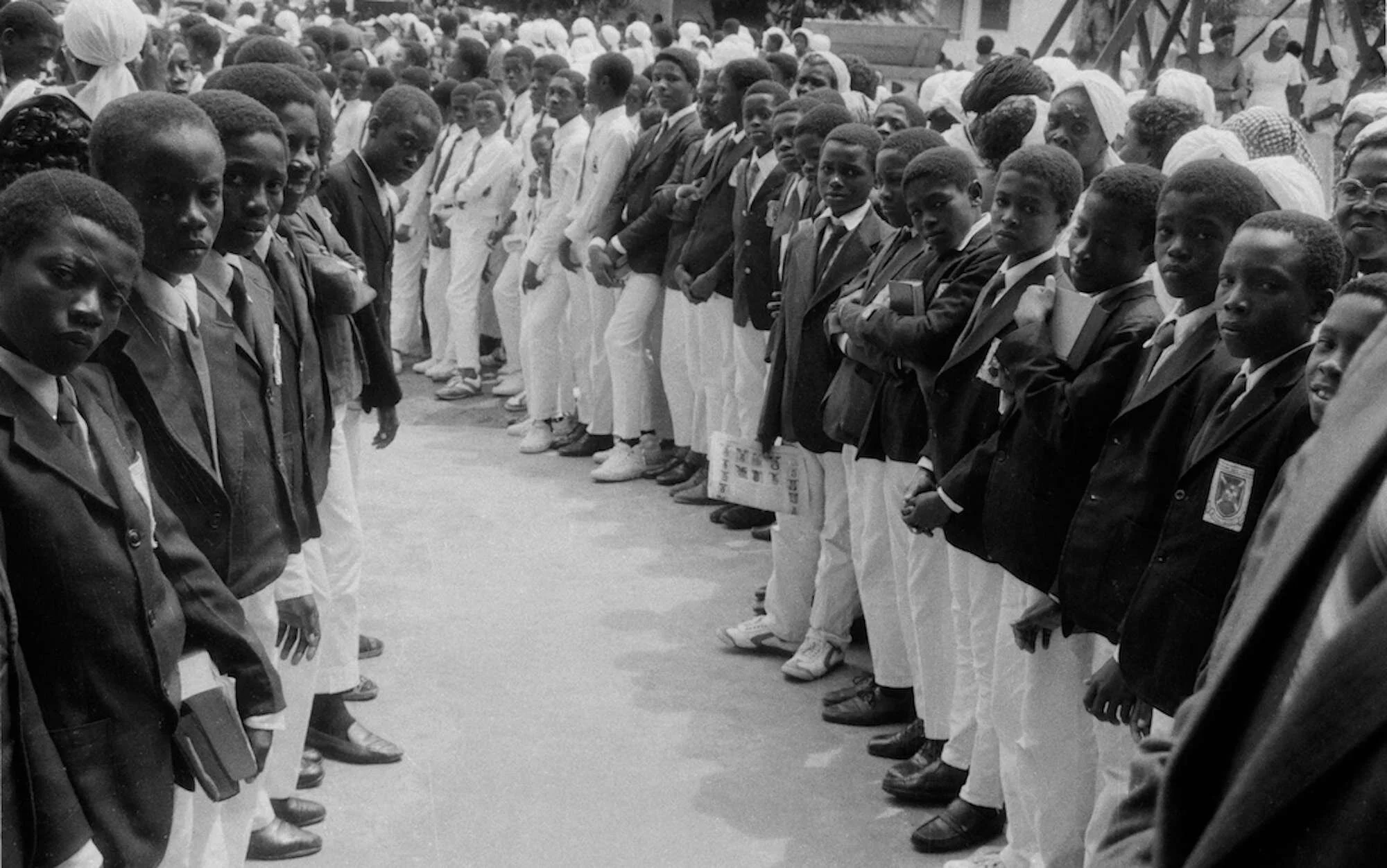

James Barnor is a man of firsts. He was the first photographer to work on Ghana’s Daily Graphic newspaper, he helped put the first black women on the covers of British magazines and he was the first to bring colour photography processing to his country; each one a considerable achievement. Born in Accra in 1929, Barnor opened his studio Ever Young in 1953 and went on to develop his career in London. His era-defining archive ranges from portraits of every day people to icons such as Kwame Nkrumah and Muhammad Ali. But it wasn’t until he was in his 80s that Barnor gained international acclaim. In recent years non-profit agency Autograph ABP has documented his works and he has gone on to exhibit globally.

This month the artist is to feature in the first retrospective show of a photographer in Ghana at the newly re-opened Nubuke Foundation in Accra. The arts space has undergone a major reconstruction to incorporate gallery, residency, studio and library facilities and become the city’s most significant cultural institution dedicated to contemporary culture. Here, Barnor shares his reflections on a seven-decade career that has witnessed the world in transformation.

You were the first photojournalist at Accra’s Daily Graphic newspaper. What kind of stories were you covering?

Almost everything, sports, politics... everything Ghanaian. Even though there were articles from overseas we covered the local stories. Most of the time I went out with a reporter but sometimes on my own. I found it easy and liked it because at school I was the editor of our school magazine for one year. No schools had magazines back then but ours did so I had an idea about doing stories and pitching.

From there I went to teach before I went into photography, but coming to the newspaper after that was easy for me. I could do my own stories when I took pictures, without anybody. I often worked not on assignment, just leading my own story, leading my own thoughts on it and getting it published.

Back then photographers were not running around with reporters, or running around with news, I was the first. Photographers weren't publishing their photographs immediately, they were not as hot as when you finish a day’s work and you are thinking about what you can do tomorrow, or how you can follow up in your last story.

You were a hungry reporter, after the next story...

Yes, you have to be!

You covered so much during that time for the Daily Graphic newspaper and for Drum magazine. Ghana was in a time of transformation as it gained Independence in 1957 and beyond. Can you reflect on witnessing such a monumental shift?

It was exciting and I was in the middle of it. When I was covering Independence Day I saw other foreign press with expensive new cameras - two or three each - and I was there with a little inexpensive camera. But with luck I got some assignments and I got good pictures so I feel proud. Today we are scanning and archiving and I'm seeing pictures that nobody has seen before from this time. In fact there are negatives that I haven't seen for years, some I haven't seen since I took them.

It has been said that your work helped ‘decolonise’ Ghana. Do you still think the country has some way to go?

Culturally we do. We should be mindful of who we are and what we should develop but people are thinking of money and other things, not thinking of culture. Politically that's another thing... People think they have been put in this position to enjoy money and power and not be the servant of the people.

What advice would you give to young photographers working in Ghana today?

I have a few ideas that I would like to pass on to local photographers to try and encourage cooperation. You should share ideas and not be afraid of your fellow photographers. We fear that if we share ideas they will get your style, your knowledge - if not your customers - so everybody is keeping to themselves.

When I was in Ghana and started out in 1949, I shared my information, I didn't fear anybody because I had a focus and I was ambitious. If you have a picture that you think is good, let others comment on it and tell you the good or the bad, then you know, and the end result could be a photographic exhibition. This is something Ghanaian photographers never do.

I wanted to have a solo exhibition here for the first time and what Bianca [Manu, curator at Nubuke Foundation] and I are doing will be a retrospective. Something like this has never been done in Ghana before.

You have always had an interest in educating others in photography and advertised for apprentices even early on in your career. What compels you to teach others?

I like working with the youth. As well as photography, I was close to all the bands in Accra, and cultural groups. So when I returned to Ghana from the UK in the 1970s, I more or less took over a group of young dancers and that also gave me a real satisfaction. I came across a magazine with an inscription that said: “A civilisation flourishes when men plant trees under which they themselves never sit.” Putting something in somebody's life, a young person's life, is the same as planting a tree that you will not cut and sell in your lifetime. That helped me in my work. I like imparting what I know, I think it's good and I enjoy it. It can make you learn more. Sometimes the more you give the more you get. That's why I'm still going at 90!

James Barnor: A Retrospective is on view at Nubuke Foundation, 7 Lome Close, East Legon, Accra from 23 November 2019 to 10 May 2020

All images are (c) James Barnor, courtesy of the Nubuke Foundation, Accra and Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

Words Alexandra Genova

Visit Nubuke Foundation

Published on 19/11/2019