The curator discusses his book, African Art Now, and his vision to democratise the art world

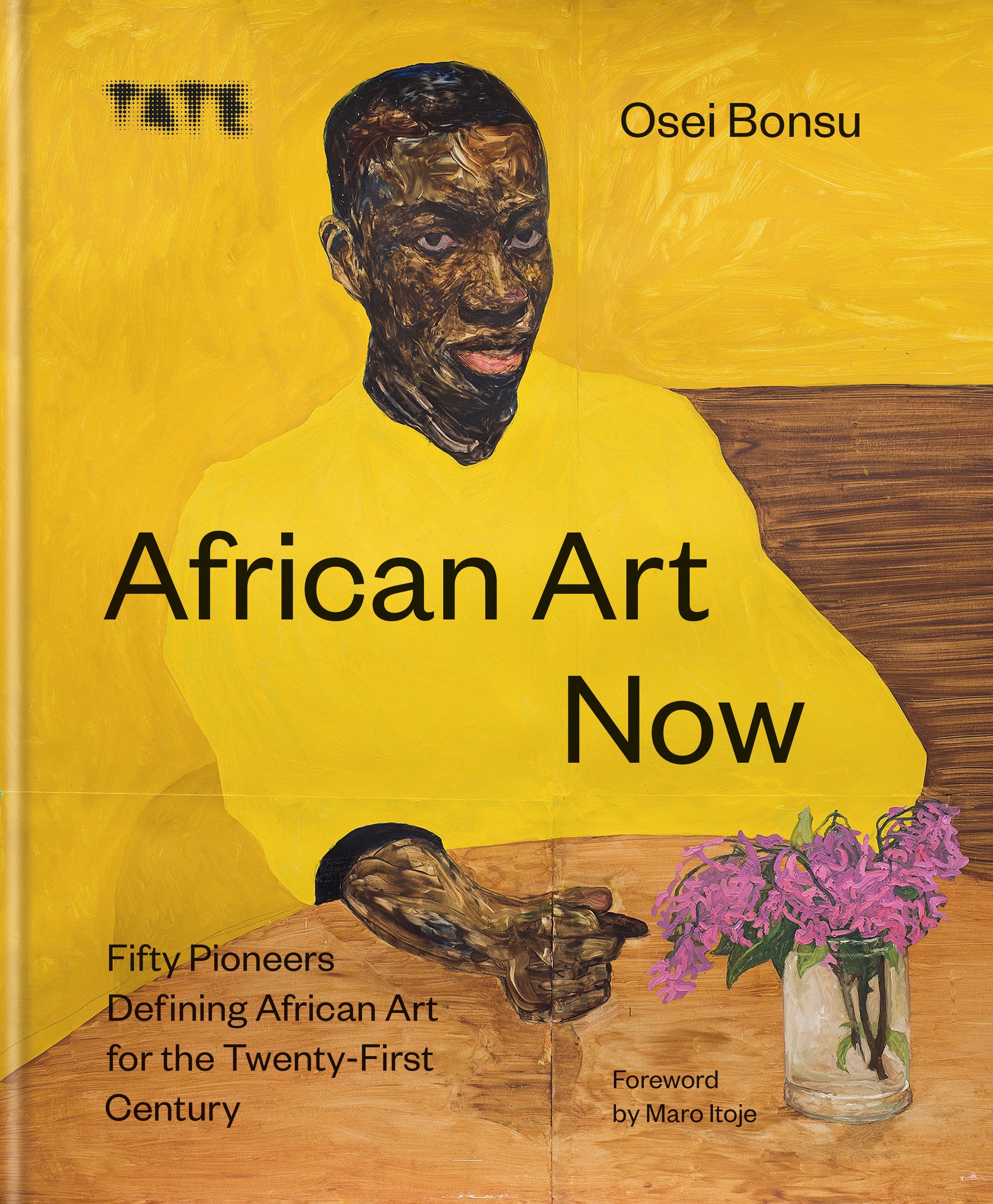

With his new book, African Art Now, Osei Bonsu invites us into the radical worlds of 50 talents who have shaped the contemporary art landscape in the past two decades. This engrossing survey rejects any limiting geographical, historical or socio-political definitions of what constitutes ‘African art’ and instead dives into the revolutionary, border-blurring themes that drive the most innovative artists working today.

This British-Ghanaian thinker has been curator of International Art at Tate Modern since 2019. Before that, he established the Creative Africa Network, a non-profit, digital platform connecting practitioners on the continent. He has also written for such titles as Frieze, ArtReview, Numero Art and Vogue and lectured at the University of Cambridge, Courtauld Institute of Art and Royal College of Art among many other endeavours. His commitment is to making space for those who have been overlooked, lesser-sung artists and under-served audiences alike, and weaving together multiple perspectives that allows art from Africa and the Global South to speak its own truths.

As such, Africa Art Now is not a didactic or singular curatorial view, or an attempt to neatly sum up a scene. Rather, he is revealing the breadth of concerns and questions that connect many of these artists, however diverse their practices and locations are. In doing so, the book surprises, delights and informs with every page. Here, Bonsu sits down with Nataal discuss what makes African Art Now so necessary.

Helen Jennings: Hello Osei. First, can we talk about how your role at Tate Modern has evolved since taking the helm?

Osei Bonsu: African and African diasporic art at The Tate had been well considered by the time I arrived but there were important areas where the collection needed development, especially in terms of what we consider to be the canon, geographical representation and the kinds of histories that weren’t seen as central to the super highway of art since the 1900s, which is the Tate’s focus of specialisation. So, the strong commitments I had from the beginning was to look beyond the artists who were readily visible in the commercial art market and think about the ways in which particular generations and localities may have been overlooked. For example, Abdoulaye Konaté has broadened the way we consider textile history and James Barnor’s photography represents the global African experience.

HJ: As the collection widens, how do you ensure it reaches new audiences?

OB: The next thing we need to think about when displaying and giving visibility to these works, is how our audiences interact with those stories we want to tell. How do we make people feel included in places that have been historically exclusive or elitist? Looking at The Tate’s location in Southwark and how diverse it is as a borough is an important starting point. It’s about moving past passive looking and making art something you can be active with on an experiential level. The more that we have this idea of The Tate as a place to dwell and to play, the more the institution performs its duty as a space of social interaction, and that’s where I see things going.

HJ: An important step then is the 2023-24 show, A World In Common. What can we expect from your curation?

OB: The exhibition focusses on photography in the collection from the 1950s to the present but not looking at it from a chronological lens with studio photography at the centre and how successive generations who have thought about portraiture in terms of its historical and social context. Instead, we’re more interested in how photography has become a space to reimagine African history; a way to reinvent many of those histories and communities that have been forgotten. It's an important idea that prior to colonial occupation, there were very rich cultures and civilisations in Africa, many of which still thrive. And it is artists who most often bring those to bear and allow us to imagine other worlds. The challenge of the exhibition is to try to ensure that it feels inclusive and also tells a compelling narrative about the state of contemporary African photography.

HJ: The moment feels ripe for your book, Africa Art Now.

OB: Yes, it’s been a time of cultural renaissance for contemporary African art. The 1980s saw the globalisation of the art world, and in the 1990s the rise of biennales gave artists from the continent a chance to show around the world. Then what we saw in the 2000s and 2010s, which is the period the book is interested in, was artists engaged with the field of contemporary African art on their own terms. They’ve formed a relationship to the idea of Africa not through an essentialist notion of identity, belonging or nationhood, but through a self-identification that can be real or imagined and articulated through a personal vision of histories, cultures and experiences.

HJ: Which artists epitomise this approach for you?

OB: I would point to Amoako Boafo (Ghana-Austria) whose project on the Black diaspora is made up of portraits of contemporary figures, cultural leaders, friends and family members, all of whom represent their own sense of home and belonging. It points to the fact that the Black diaspora is ever-expanding and many African artists feel an identification with it. His paintings are also made in a timeless context, which typifies the way African artists are exploring representation without the burden of having to include cultural references to Africa. I was conscious of putting a work by Boafo on the cover because in the last five years, no artist has been more influential in terms of informing how other young painters are working and reconceptualising the medium of portraiture.

Also looking at ‘African-aity’ is Michael Armitage (Kenya-UK) who works with found images – both documentary reportage and classic art images from figures like Manet and Gauguin – to address issues such as the anti LGBTQ laws in Uganda and how people are deeply affected by these realities. One of the inspiring things is that many people in the book are dealing with these hard-hitting social and political themes but it’s not immediately obvious. You have to look beyond the surface and that’s the power of African art now.

HJ: What was your approach to selecting and presenting artists in the book?

OB: I thought of it as creating an ever-expanding constellation. I wanted to ensure there was a wide range of social and political themes being explored and to look at as many forms of expression as possible in order to get away from the art market view that painting and sculpture has more value than other mediums. Another aspect was thinking about geopolitical and geographical representation, which is one of the hardest challenges. We weren’t able to represent every African country but we are considering the cultural through-lines that unite artists on the continent.

I was interested in this book in not being overly concerned with giving a definition to African art from an essentialist or ethnographic standpoint as it has been so often categories in history and instead try to focus on what artists are saying about their work. I wanted it to feel like a polyphonic reflection of African art rather than a curatorial reading of the continent.

HJ: Your introduction in the book outlines five thematic constructs that help to guide us through the work of those artists profiled. Let’s start with Shifting Identities and The Family Portrait.

OB: Shifting Identities is the ways in which artists think beyond cosmopolitanism to look at expanding identifications of gender, race and class can be interrogated now in a way that wasn’t possible for generations prior. It’s something I associate with how the history of studio photography and has expanded into painting. Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, who herself relocated from Zimbabwe to South Africa to the UK, explores political and social rupture in her own family and how the family photo album and social media can be reanimated through painting.

It's a topic that came up with Toyin Ojih Odutola (Nigeria-US) who uses the role of fiction to cultivate all of these possibilities of being in a world that isn’t tethered to a particular time or place. This can create time travel through art work and draws on the possibilities of afrofuturism. Where we have to be cautious is that afrofuturism is a concept explored more readily by artists in the diaspora because it’s made up of a series of provisional fictions that are about cultural or artistic lineage rather than a direct experience of Africa. What we should be doing more readily is thinking about the lived experience of those based or born on the continent as a point of departure for understanding Africa, not through the fantastical but through the every day.

“The more that we have this idea of The Tate as a place to dwell and play, the more the institution performs its duty as a space of social interaction”

HJ: I thought it was interesting that you have not highlighted afrofuturism specifically, given its thematic popularity across creative disciplines from art to fashion to film. And I agree, it can become problematic.

OB: The idea of ‘future-ality’ isn’t cliché images of what we imagine the future to look like through a western lens. African artists have always been ahead of their time, and their work has always been adventurous, challenging and expansive. But often it is associated with an ancient past, and fetishised for that reason.

HJ: Which leads us to the next theme, Postcolonial Dystopias.

OB: Rather than this strong focus of utopian ideas of pan African unity, we’re looking at when the dream after independence goes wrong, and artists find themselves trying to find meaning in a political landscape that is hollowed out of any empathy. Igshaan Adams (South Africa) is thinking about the impact apartheid laws had on the landscape and how that imposed ongoing power imbalances and racial hierarchies that still exist today.

HJ: Then onto Future Ecologies?

OB: This isn’t about environmentalism or green politics. It’s the ways in which artists are using found materials and resources available to them to make a more sustainable idea of what art could be, while also investing that material with a new set of political and social possibilities. You could look to Moffat Takadiwa (Zimbabwe) who uses toothbrush hairs, bottle caps and the tops of spray cans to create woven tapestries. For a long time, there was a stigma around using such materials, almost as if it was a secondary practice or a reflection on the economic state of the continent. In fact, these artists have found incredibly innovative, powerful ways to reinterpret these materials that now speak to the dynamism of African art and a future in which these artists will be leading the charge as our planet remains under such environmental and geopolitical strain.

HJ: Finally, Reclaiming History.

OB: This speaks to the politics of restitution, which is too focussed on an object-based discourse around reclaiming an irretrievable past. I don’t think it’s useful to think in terms of objects being relocated being an end in itself. What happens when these objects are taken is that it removes a social, historical and cultural memory. Many artists are placing an emphasis on how performance, photography and film can be ways to enact culture beyond the physical object. Zina Saro-Wiwa (Nigeria-US) is looking at the destruction of the Niger Delta by the oil industry and the local people working against this environmental threat. And Edson Chagas (Angola-Portugal) is thinking about a reinterpretation of the African object in relation to passport photos and the fact that as humans we are policed by national borders and geopolitical structures every day.

That opens up this idea that restitution can be about how we want the world to become more of a shared community and embrace a continuity of cultural recognition. Artists are reacting to the challenge of creating new histories in the absence of a grand historical narrative. Rather than building that historical narrative through restitution, they are coming up with very inventive ways to appreciate contemporary art in this moment. Building institutions isn’t the only way to experience culture.

“Many artists are dealing with hard-hitting themes but it’s not immediately obvious. You have to look beyond the surface and that’s the power of African art now”

HJ: Speaking of institutions, the book includes an index of emerging organisations, community-driven projects and artist led spaces on the continent. Does this point to the future of African art that is not reliant upon international recognition?

OB: I set up the Creative Africa Network in 2015 as a resource for artists to connect with curators and gain more clarity around the commercial art market, institutional commissions and residencies. Since joining The Tate we’ve been less active but so many artists in the book have now established their own institutions, such as Ibrahim Mahama (Ghana). The index helps in that it is made up of organisations that would benefit from the visibility that the book offers and in turn could be partners for projects with institutions like The Tate which need to think more laterally about how they approach collaboration. Does it always have to be a large-scale touring exhibition or could it be more about partnering with organisations on the ground? We know there are significant imbalances. So often African artists are celebrated in programmes off the continent rather than on it. It’s something that needs to be given more attention and a point of passion for me.

HJ: You also take time to lecture and teach the next generation of art professionals. This too builds the curators of tomorrow.

OB: Being someone of British Ghanaian heritage, I have to take seriously the privilege I have in the field of contemporary art predicated on a level of access that most young African curators don’t have. So, giving mentorship for anyone interested in being part of the visual arts is another point of passion. With the book, I’ve tried not to over intellectualise the work to the point that the core ideas get obscured for those who might be looking at African art for the first time. I want, as best as I can, to share my knowledge and in turn empower young curators on the continent to do their own research and mine different fields of cultural production. One of the legacies of this project would be if it inspires people not to look at the continent at large, as this book aspires to, but look at art in specific areas where more rigorous scholarship is needed.

HJ: Beyond books and bricks and mortar institutions, African art is increasingly thriving in the digital space. Where do we go from here?

OB: As we think in more democratic ways about how people interact with art, it’s exciting that many artists are now growing their practices by reaching audiences via social media. It creates more of a level playing field for those not based in the geographic centres of art – London, Paris and NYC. Why can’t Accra or Cape Town be a future art capital? It’s time we think of these destinations as being part of a very critical shift in the power dynamics of the global art world.

HJ: Hear, hear, and thank you!

African Art Now by Osei Bonsu is published by Ilex Press / Tate. Discover it here.