Sharjah Art Foundation is nurturing the UAE’s contemporary art scene while promoting social justice for all

When programming the events for The Sharjah Art Foundation’s March Meeting, its president and director Hoor Al Qasimi clearly had Palestine on her mind. As an esteemed foundation wedded to creating a dialogue between contemporary artists from the MEASA region and those from around the globe, this year’s annual gathering ruminated on the theme of collective practices of artistry and community-building that advance social justice. As such, it featured speakers from Palestine and its diaspora on most of the panels including performance artist Jumana Emil Abboud, musician Samir Joubran and Nöl Collective founder Yasmeen Mjalli. In addition, the exhibition, ‘In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine’, was running concurrently (read our review here). Alongside a gamut of timely talks, performances and workshops, the March Meeting was also a last chance to see the much-hailed Sharjah Architecture Triennial curated by Tosin Oshinowo. Plus, a number of major exhibitions focussed on art from the north, east and south of the African continent were revealed.

One major highlight was ‘Gavin Jantjes: To Be Free! A Retrospective 1970–2023’, which celebrated the development and diversity of the South African painter’s work, including his most recent pieces created while in residence in Sharjah. Arranged chronologically, it was almost like a visual representation of the country’s own history with earlier works themed around global solidarities, struggle and Black liberation. Born in 1948, Jantes’ life was shaped by apartheid, and given the most recent escalation of Israeli violence against the Palestinian people, it’s hard to not feel that it remains his most pertinent.

From hyper local work that reflected his own community’s fight for equality, such as A South African Colouring Book, No More and Amaxesha Wesikolo ne Sintsuku (School Days and Nights) to a wall of colleges that explored different liberation movements on the continent, For Algeria, For Ghana and For Mozambique, these pieces could all have been created today. Including works that looked even further afield, he highlights the links between the struggles of the Global Majority. For example, The First Real AmeriKan Target calls attention to the persecution and slaughter of indigenous people on the American continent.

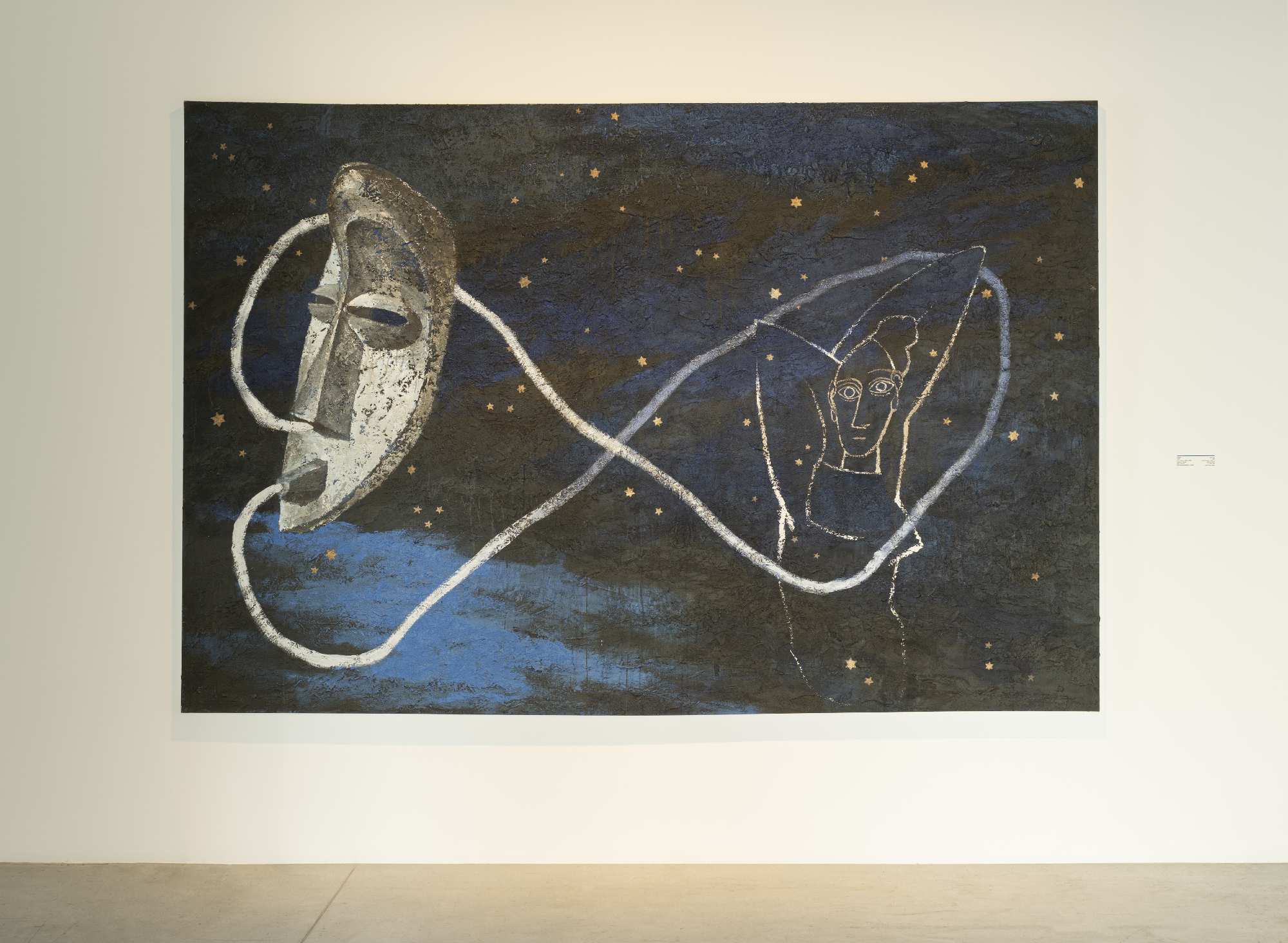

During the 1980s, he turned his eyes to cosmology and created the Zulu series, stating, “the heavens are the most neutral space – no nations lay claim to the heavens. They are undefined…and are accessible to every human being.” And fast forward to now, he’s been looking to the seas and creating vast pastel-coloured canvases that you want to dive into because, as Palestinian poet Marwan Makhoul writes, “In order for me to write poetry that isn’t political, I must listen to the birds and in order to hear the birds, the warplanes must be silent.”

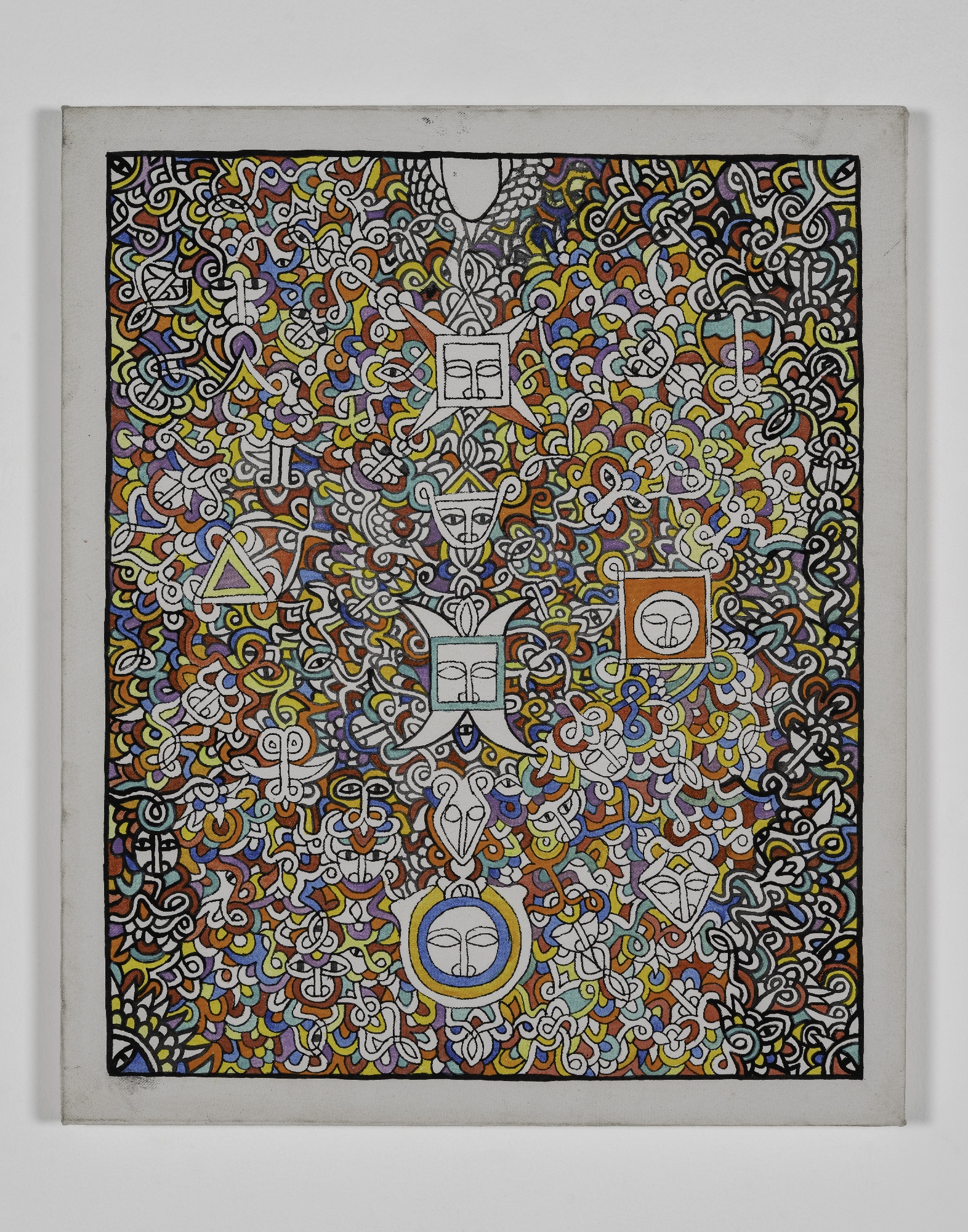

Meanwhile, slightly out of town, ‘The Casablanca Art School: Platforms and Patterns for a Postcolonial Avant-Garde (1962–1987)’ recognised Morocco’s legendary art movement. This exhibition made you want to drop everything and hop on a flight to the sprawling city, as well as find some sort of time travelling device to journey to the postcolonial period, which was so rich in hope and fearlessness. Both a literal educational establishment and artistic movement, The Casablanca Art School reimagined Moroccan art within the context of modernism. It placed Amazigh art at the same level as contemporary European art, which had almost certainly been inspired by the former.

The exhibition positioned the works within their historical contexts, showcasing the political side of these colourful and abstract paintings including the school’s emphasis on public art. They developed street exhibitions that were both open to all and acted as a protest against the French Salon du printemps, which categorised Moroccan art as ‘naive’. The Open Air Museum, developed in the late 70s by Mohamed Melehi and Mohamed Benaïssa and continuing to this day as an annual festival of art, was also highlighted in the show – as was a space dedicated to the growth of Pan Arab solidarity from the same decade highlighting the work of Mohamed Melehi and Mohamed Chabâa, who designed the posters for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, organised by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation.

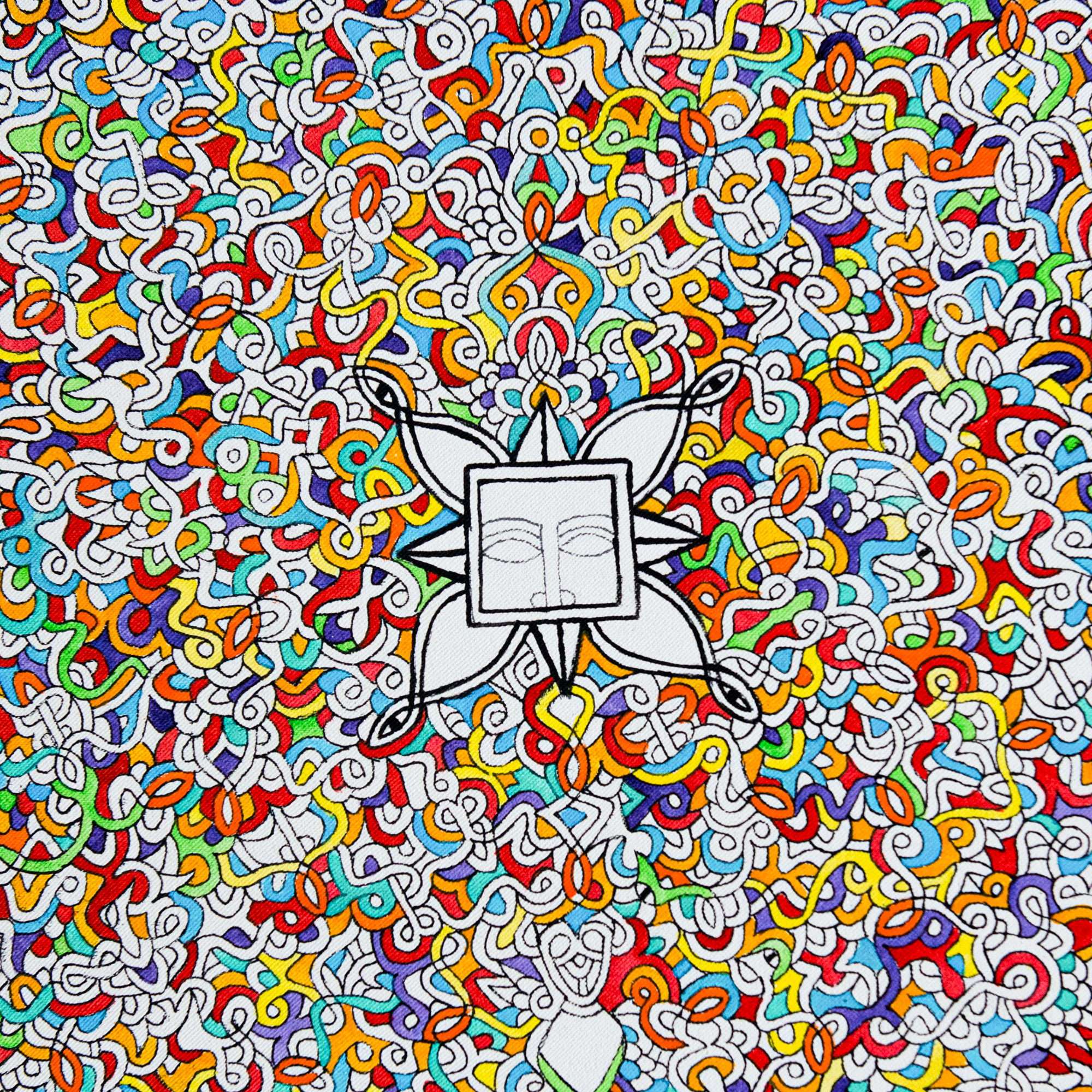

Back in the centre of Sharjah, Henok Melkamzer’s traditional telsem art was on show. ‘Henok Melkamzer: Telsem Symbols and Imagery’ is the Ethiopian painter’s largest solo exhibition to date and attempts to reframe eurocentric perceptions of telsem-based art as purely spiritual and, instead, properly categorise it as modern art. Melkamzer’s father and grandfather were both telsem healers and the artist uses his work to both preserve the ancient practice and open it to new audiences. Impossibly intricate, each of his paintings are imbued with spiritual and philosophical meaning. Acting as living objects, they are modern works of art that communicate an ancient, healing knowledge. One that the world is in serious need of right now.

Read our story on the Sharjah Art Foundation exhibition ‘In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine’, here.