Charlotte Yonga on capturing the mercurial nature of love and belonging in Madagascar

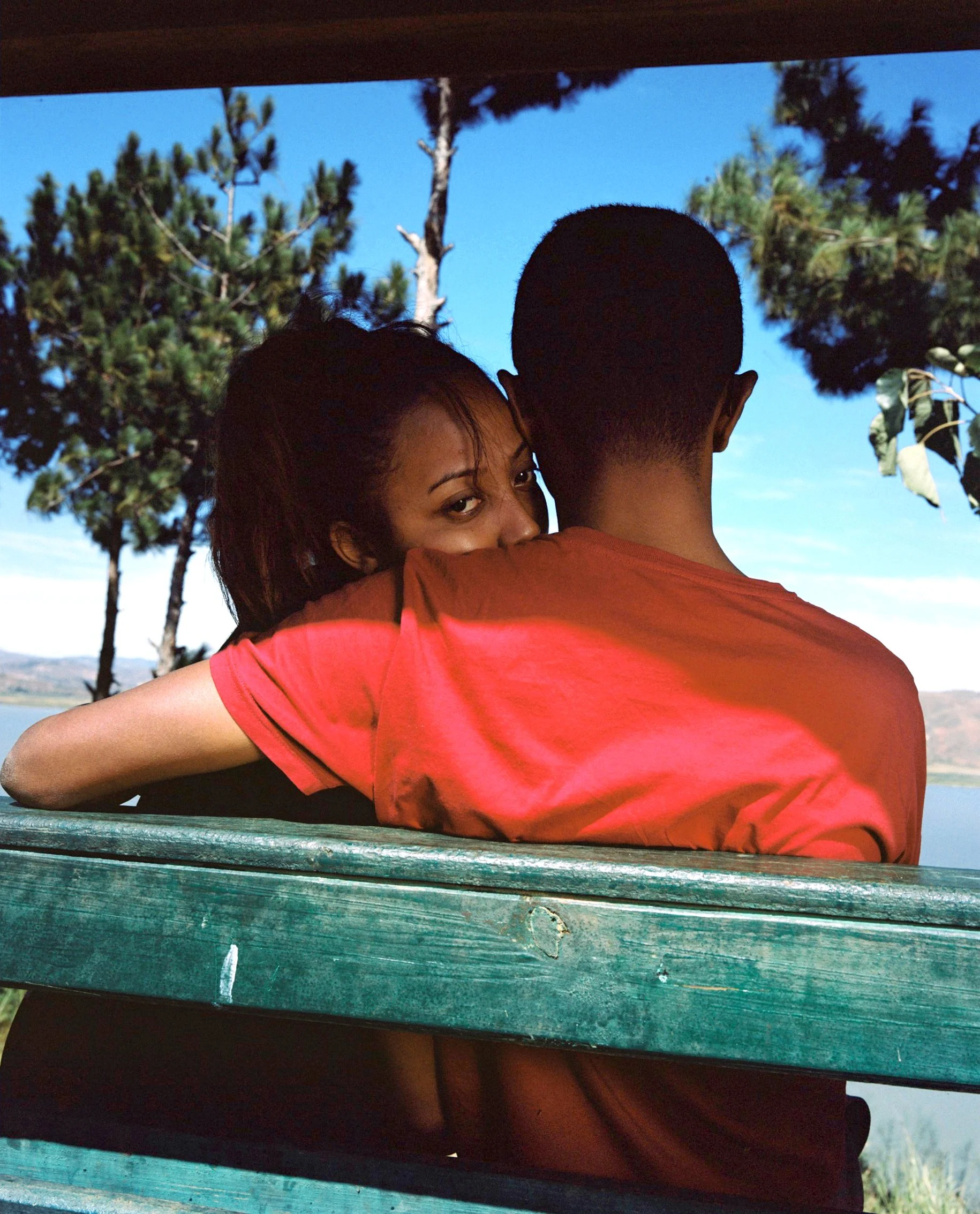

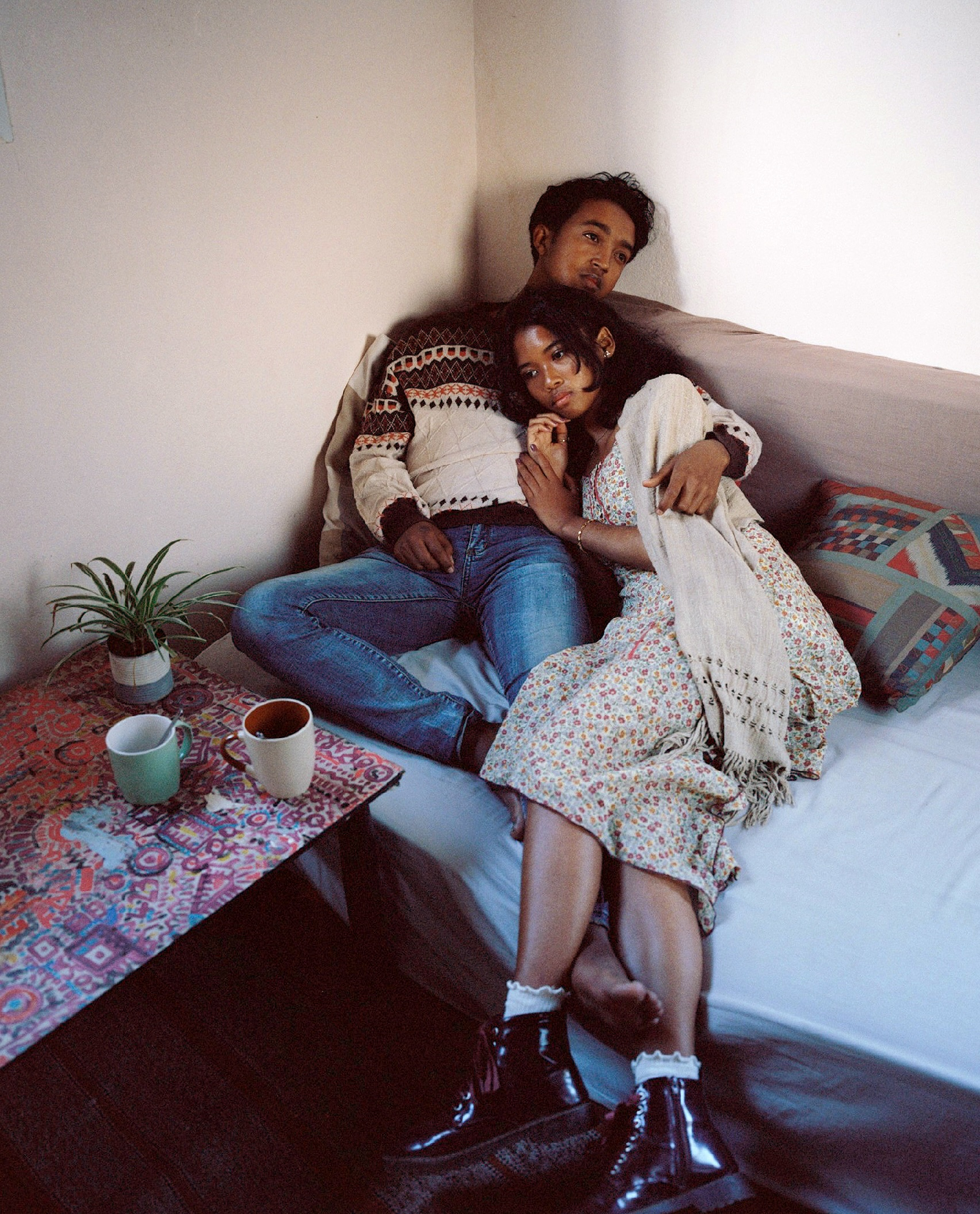

Charlotte Yonga’s latest photographic series, ‘(Tsy) Possible’, holds the stillness of a secret, like a moment suspended mid-breath. Each image feels as though you’ve just stepped into a private scene: an embrace, an argument, a pause heavy with emotion. And through them, she offers fleeting yet profound glimpses of Malagasy life and love. Created during her 2024 residency at Fondation H in Antananarivo, the series continues the Franco-Cameroonian artist’s ongoing meditation on belonging and representation across African and diasporic geographies. Her 2021 series ‘Naam Na La’, made in Dakar, examined youth, romance and identity in West Africa while her 2023 work ‘Salt Wind’ was developed in Malta and honoured open and shifting relationships. With ‘(Tsy) Possible’, she shifts her gaze towards the Indian Ocean, tracing how the fragility, performance and politics of intimacy is shaped by Madagascar’s social and geographical landscape.

Speaking to us from her home in Barcelona, Yonga explains this visit, her first to Madagascar, was both disorienting and captivating. “It was not easy in the beginning,” she recalls. “The culture is very specific to Madagascar, and I went there with my West African references – it was very different.” Travelling with her four-year-old son added another layer of intimacy and vulnerability. But over time, her connection to the island deepened and by the end of the three-month visit, she had fallen for the island nation. “It wasn’t a crush – I was heartbroken to leave,” she admits, with her fascination and affection for the country now evident in each image.

The title, borrowed from a popular Malagasy song by Tiji Negga featuring Ngiah Tax Olo Fotsy, which reflects on the disappointment of a romantic breakup, plays with the idea of negation. In Malagasy, tsy means ‘no’ or ‘not’ while possible, a French import, has no local equivalent. “The title expresses this tension between freedom and constraint,” Yonga explains. The parentheses around the negation then turns it into a quiet question: “What if the impossible, the prohibitions, the obstacles became points of departure?” she asks in her artist statement. The series does not promise resolution; instead, it lingers in the space between hope and hesitation, between tsy and possible. And in doing so, that tension becomes a visual language.

Across a suite of lush, cinematic photographs, Yonga explores fitiavana, a Malagasy word that gathers together romantic love, familial love, friendship and the simple love of life. She digs into these different emotional bonds while also tracing how love is shaped by colourism, class, tradition and societal expectation. “For me, love is a way to understand another culture; [their] political and social context,” she says. “Society impacts our way of loving, of getting attached, of encountering relationships.” In Madagascar, she found that affection felt both tender and obstructed. For example, “You can’t marry who you want because of family pressure.” The island’s vast, fractured geography, also captured in the series, seemed to echo this emotional landscape. “Even if you have someone you love in the north or the south, the roads are bad, even the distances can be a problem.”

Love here, she realised, is shaped by roads and roots — cultural, class and ethnic. It exists in the tug between pride and rebellion, between belonging and want for freedom. “They are far from everything and very close to their culture, and proud of it,” she notes. Among the youth especially, she sensed both resistance and yearning, a pull toward ancestral customs and a personal desire for imported models. “I felt this impossibility but also a great desire to break it,” she reflects softly. “I think they are very romantic but also reserved and discreet.”

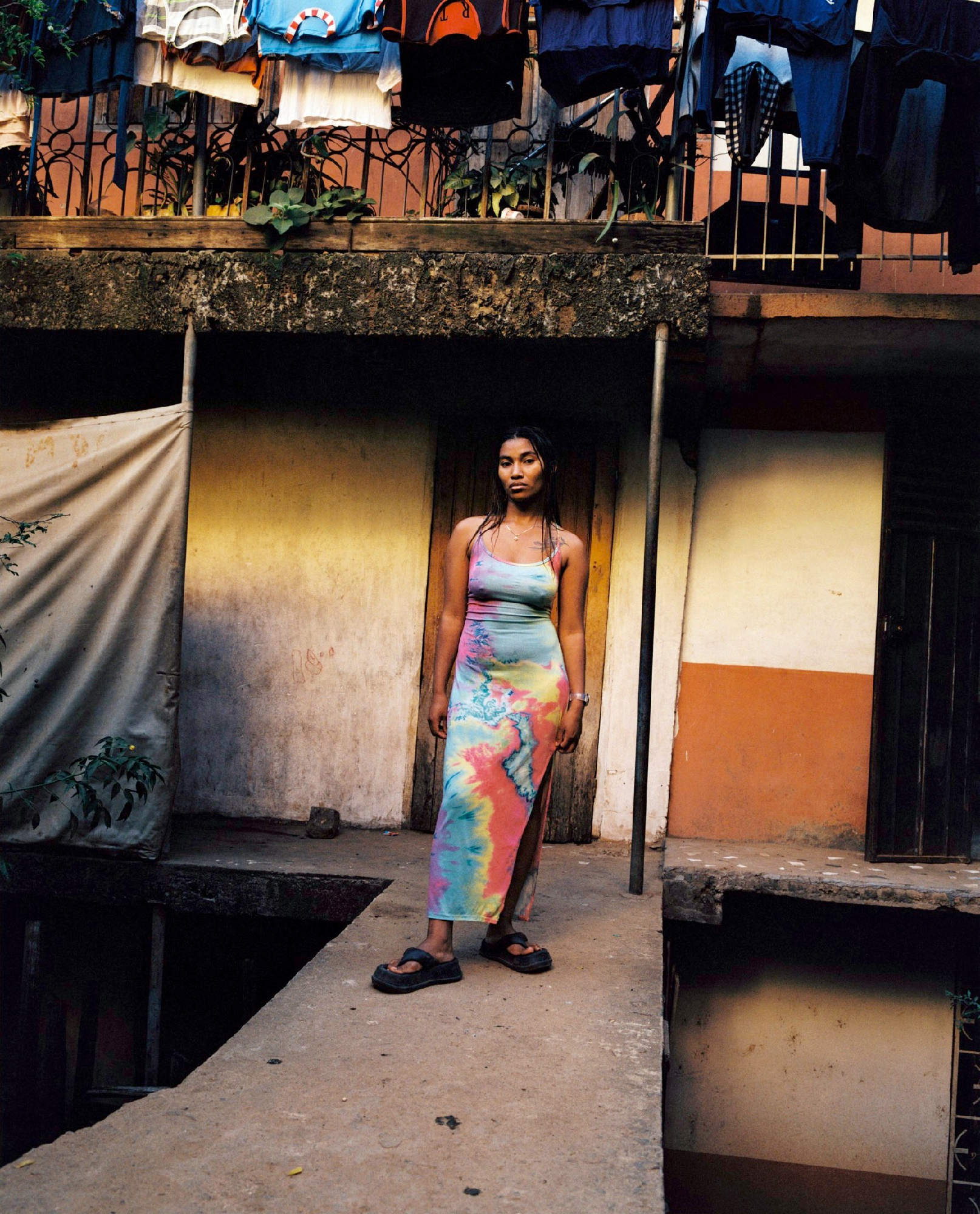

Shot on a Mamiya 7 film camera, her portraits feel warm and humid, layered with ambiguity. Oscillating between fiction and documentary, they are also carefully constructed, with false couples and staged interactions shot in their own homes and personal spaces. She gives her sitters emotional cues and narratives they can inhabit yet the relationships remains elusive, each scene blurring the lines between melancholy, boredom and yearning. “I want people to imagine how it can be [in Madagascar]— to be young, to be romantic, to be disappointed or frustrated about love, as everyone can, and I like you to have many interpretations of one image,” she smiles.

“Society impacts our way of loving, of getting attached, of encountering relationships"

She works intuitively, discovering her subjects through encounter rather than casting call. “I find my models everywhere I can: in restaurants, on the street, at the foundation,” she says. “I want to be open to anyone.” Approached with upmost care and patience, she strives for respect while shooting, working with what they offer her in the moment. “When you shoot someone you take something from them so it’s not easy to find serenity. I just want them to feel that I’m trying to make them beautiful, not like models, but in their own way.” The results speak volumes as each subject radiates grace and authority. Their gaze never feel stolen; it is shared, like we’re being let in on something that would otherwise be kept under wraps.

“I want people to imagine how it can be in Madagascar to be young, to be romantic, to be disappointed or frustrated about love"

As a Franco-Cameroonian artist, she is attuned to the lens. “Maybe being from Africa too, helps me to find my legitimacy. If I was a white person, it would bring more issues. And as a woman of colour, I connect more easily.” Still, her camera’s focus deliberately stops at one metre, making her images feel intimate but never invasive; near but not claiming. “It keeps a distance with my models to protect them,” she says.

Yonga’s landscapes feel equally permitted as she finds beauty in the seemingly mundane: a single flower, lace curtains drifting from a window, a piece of fruit. Madagascar’s lush forests, ochre earth and dense air all seep into her images. “Nature is not a mere backdrop but a sacred and active presence,” she notes in her artist text, framing these surroundings as a network of care and love for oneself, for others, for community, and for all living things. Throughout ‘(Tsy) Possible’, love stretches outward from family and community to land and sea as she brings the evident connections between emotions and ecology to life. “I really think love is everywhere,” she says “and you can share it with anyone you cross in your life.”

Completing the series has given her an understanding of love that is both idealistic and pragmatic. “Love is the noblest feeling but also the hardest,” she says. Neither naïve nor indulgent, it is a discipline that requires “resistance and resilience.” As ‘(Tsy) Possible’ reveals, it is shaped by social expectations, cultural pressures, geographies and the sheer effort required to sustain it. “It’s not easy to be free to love as we want, and even when we find it, it’s still work to maintain.”

Yonga speaks of returning to Madagascar, thinking often about her friends and the people she photographed, (“I share their hope for the country to change.”), and of continuing the project across other islands of the Indian Ocean. No matter where this ongoing inquiry takes her, the artist’s work will continue to insist on ambiguity as a form of truth. Her portraits neither confirm nor deny but allow, her muses neither trapped nor free. To look at ‘(Tsy) Possible’ is to feel that the impossible has already begun to shift.