In conversation with the South African painter as his work goes on view in London

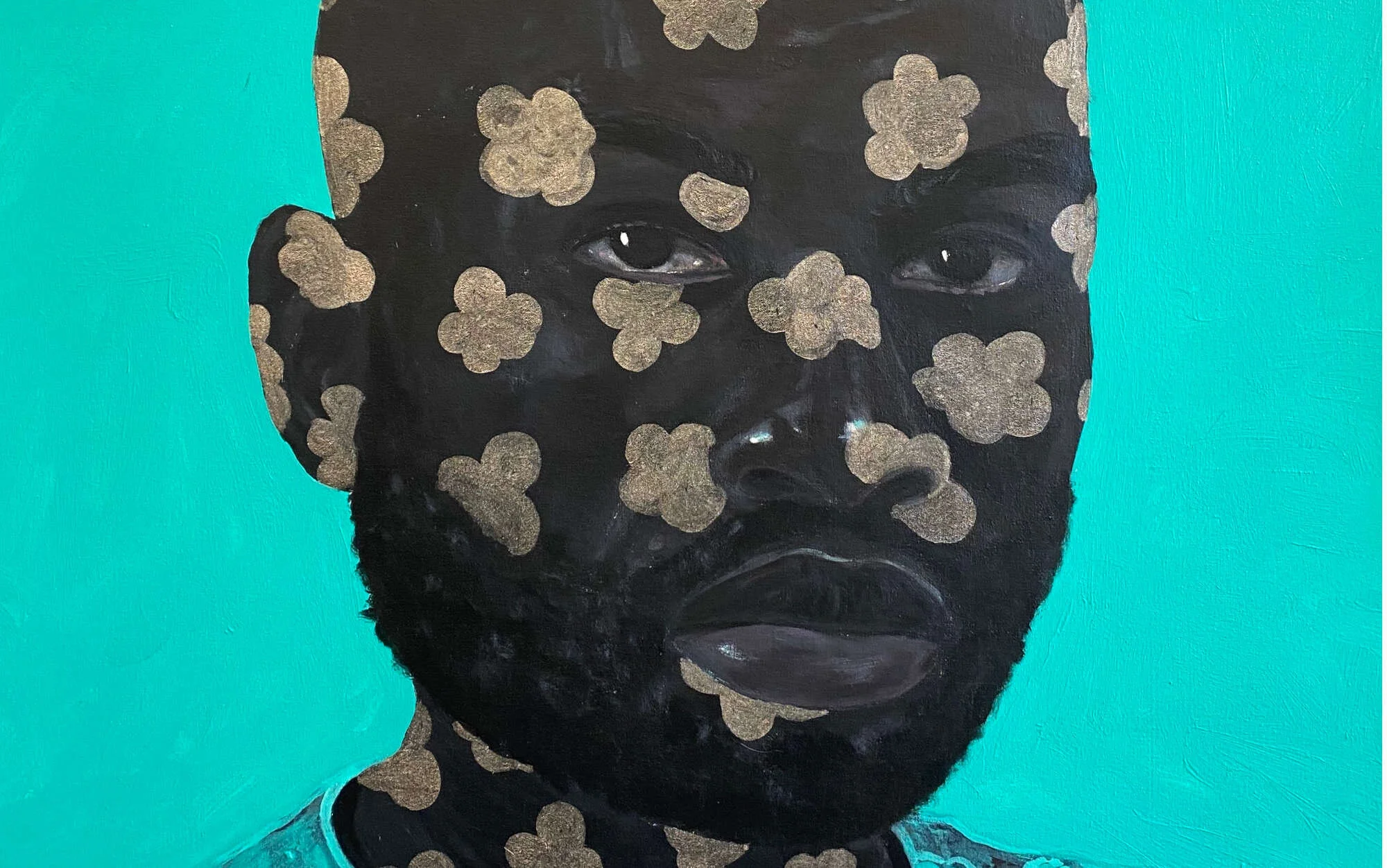

In Wonder Buhle Mbambo’s otherworldly portraits, the viewer encounters calm figures in states of repose. Their dark, luminous skin shines out against bold expanses of colour while Mbambo’s deftly applied acrylic textures plant magical flowers across the canvas. What strikes you first are the richness of his hues – the deepest black, the brightest turquoise, the most regal gold. And then it’s the purity of his muses, who are youthful, serene and self-possessed; meeting your gaze and happy just to be.

The South African artist’s paintings typifies the theme of The Medium is the Message, a group show at Unit London that explores the role pigment plays in the expression of identity. Showing alongside 17 other emerging artists of African descent, his transcendental approach counters expectations that Black artists must always tackle political, social or racial themes.

“This exhibition veers away from the performative power of the image and ponders existence beyond representation,” explains the show’s curator Azu Nwagbogu. “The Blackness presented here is authentic, quiet, and confident… Their art unveils many facets of black existence that encompass play, solitude, contemplation and a range of human experience with approaches that do not kowtow to exoticism, but rather reflect the communities from whence they were birthed.”

Born in the village of Kwangcolosi in Kwa Zulu Natal, Mbambo relocated to Durban to study as part of the Bat Centre residency programme in 2010 and then the Velobola Apprenticeship programme at the Durban University of Technology. He enjoyed his first solo show at Durban Art Gallery in 2018 followed by a second at PhilipZollinger Gallery in Zürich. In the same year he was granted the Royal Overseas League Scholarship to become artist in residence at The Art House in Wakefield, and his star has been rising ever since.

Here we talk to him about his soulful and joy-giving works.

Please tell us a little about your upbringing.

I grew up in the countryside around very powerful females. My mother is a spiritual healer in the community and I was often under my grandmother’s guidance. I was a creative kid who was always making charcoal drawings on the walls of the rondavel houses.

How did you come to focus on art?

When I finished high school, I wanted to be a psychologist but my grades weren’t good enough. While I was trying to qualify, I discovered an art centre in Durban and spent most of my time there, so someone said I should focus on art instead because I can use it in the same way [as psychology] as part of healing. I was interested in that conversation and enrolled in art school.

How did your practice develop?

It’s been a journey. In my village at nights it was very dark, which introduced me to silhouettes - of the mountains, of people moving by - and the full moon allowed me to enjoy the stars. It was all so appealing to me as a kid. When I moved to the city, I experienced a different life. I had to learn the language of the streets but still carry with me my cultural teachings. I realised the value of my roots that protected me in this chaotic sphere, and that is what shaped the work you see now.

In what ways?

I started with charcoal drawings and then acrylic paintings that got away from the political landscape of the city and created a safe space where I could feel my spiritual guidance wasn’t diluted. I started depicting myself as this guy in a space where there are no buildings or objects you could identify with. It’s always a plain, illusive space where anything is possible and where I can start to borrow from my mum’s spiritual materials.

Hence the flower-like star symbols.

They represent a very special flower, which when you burn it, serves as a medium to communicate with your ancestors. You can say your wishes and dreams. I do the same with my work. I charge the paintings with these stars so that wherever it’s going, it will purify that place.

What role does colour play in your work?

The figures are so dark and the pigments so black as a way to reflect the night time silhouettes of my youth. I want to invite those things from home when I paint. My work is very personal and pure in that way. But I am not trying to find my identity or myself through painting. I’ve been well taught who I am and where I am from, which has built my self-confidence.

Is it fair to say though that your portraits are a celebration of Black people?

Yes they are, and obviously now the work has gained a bigger narrative because of what is happening with Black Lives Matter, but I am not overtly trying to align it to any contemporary topics. As I continue to work and travel, what I always say is that my paintings are a conversation with the world. I’ve met so many beautiful souls from different backgrounds and countries so that alone means I have a greater understanding of different perspectives.

Who are your sitters?

I would say it’s 50 per cent come from my imagination and 50 per cent are drawn from photographs I take when I see someone striking. In my 31 years, a lot of people have passed my eyes and so there are faces that stick with me and become my chosen ones.

Tell us about one of your paintings in the London show, entitled Umthobisi.

Umthobisi is a portrait of my friend. His name means ‘someone who comforts others’ and his personality very much goes along with the name. He has a gift for making people feel calm. I took his photograph three years ago and he really didn’t want to be immortalised like this! But I wanted to highlight how our given names impact on us as we grow. It’s like that for me. Buhle me means grace or to shine, like my work.

What are you working on next?

I am part of a show in Lagos in November, also curated by Azu, and then I will have my third solo show at BKhz gallery in Joburg in December. I am just stepping into the global arena in an era when Black artists are being appreciated and doing big things. Some say that the African art scene a bubble that will burst but I believe it’s our time to be seen and heard.

The Medium is the Message is on view at Unit London, until 15 November 2020