The party of a generation in Abidjan where the city's creatives come to dance

Until dusk slightly cooled that sweltering Sunday in February, the Club House Le Vallon was what it has always been, a complex where well-off families can swim, play tennis, or enjoy a meal in a tranquillity in Vallon, one of the most coveted neighbourhoods in Abidjan. As the last families departed, one tennis court remained brightly lit, its clay surface covered with colourful woven rugs, low armchairs and decorative plants, its air streaked by water misters; with mammoth sound-systems emitting propulsive beats to the delight of the hippest crowd I have ever seen in this bustling Côte d'Ivoire city.

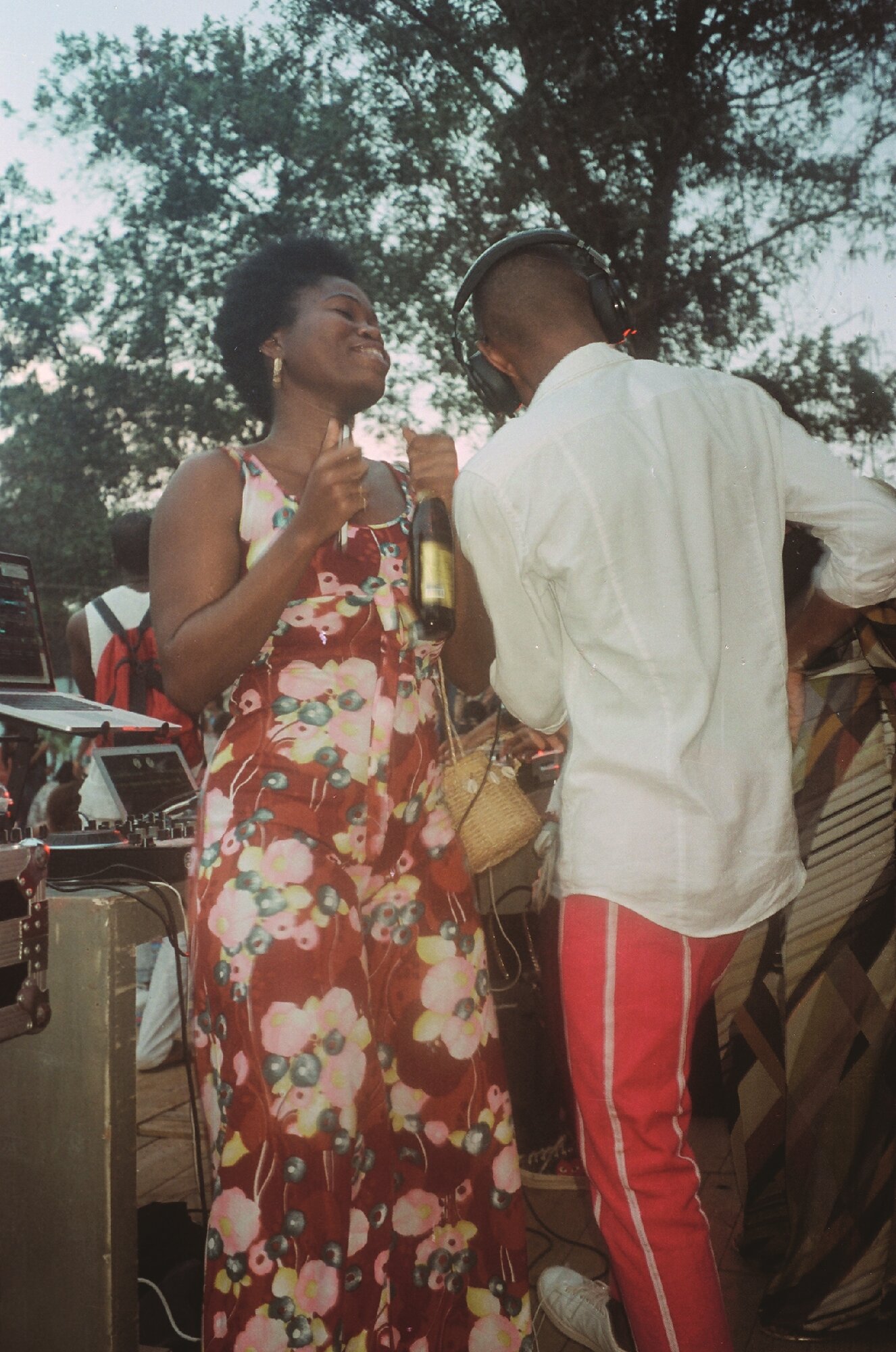

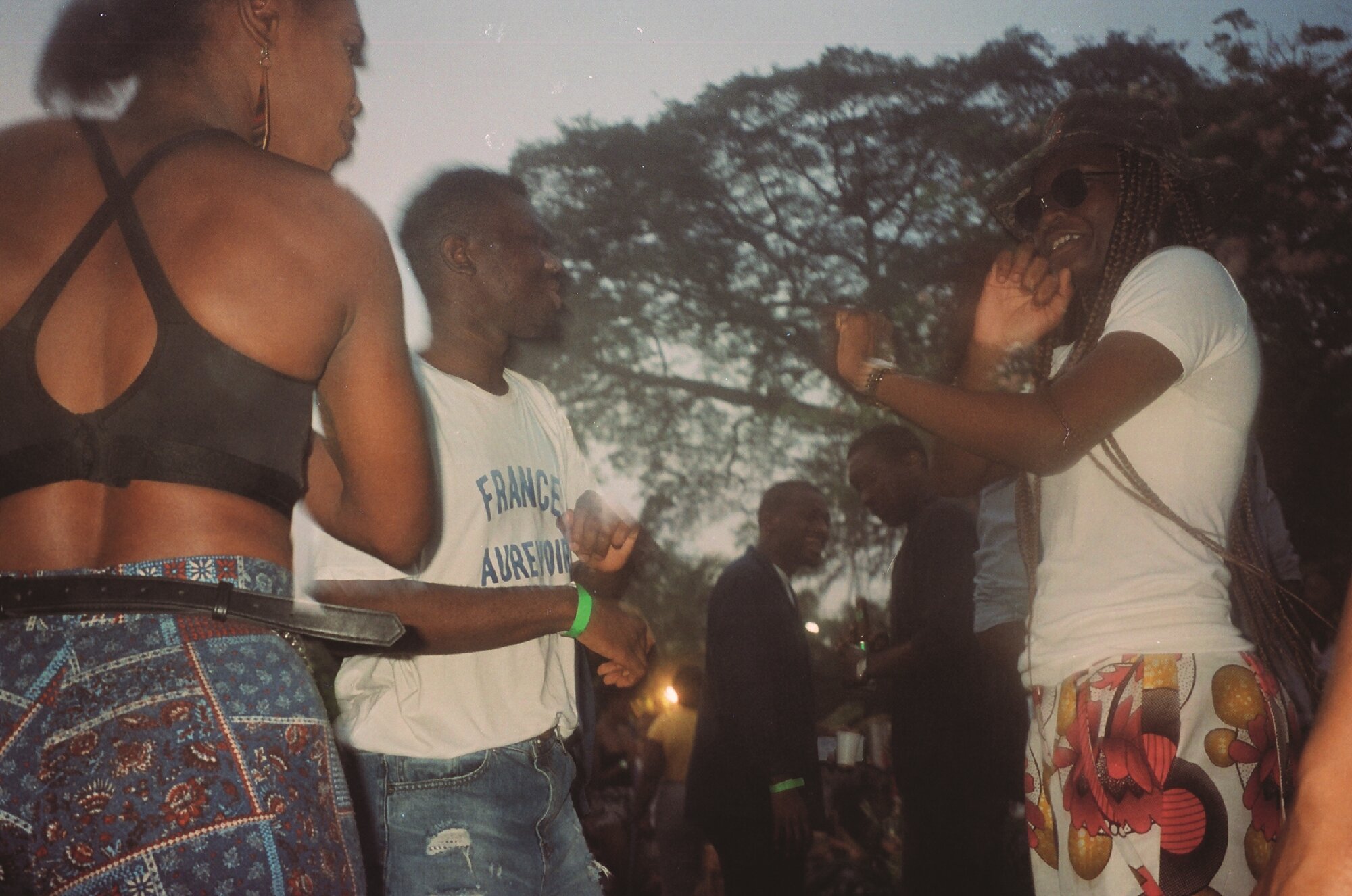

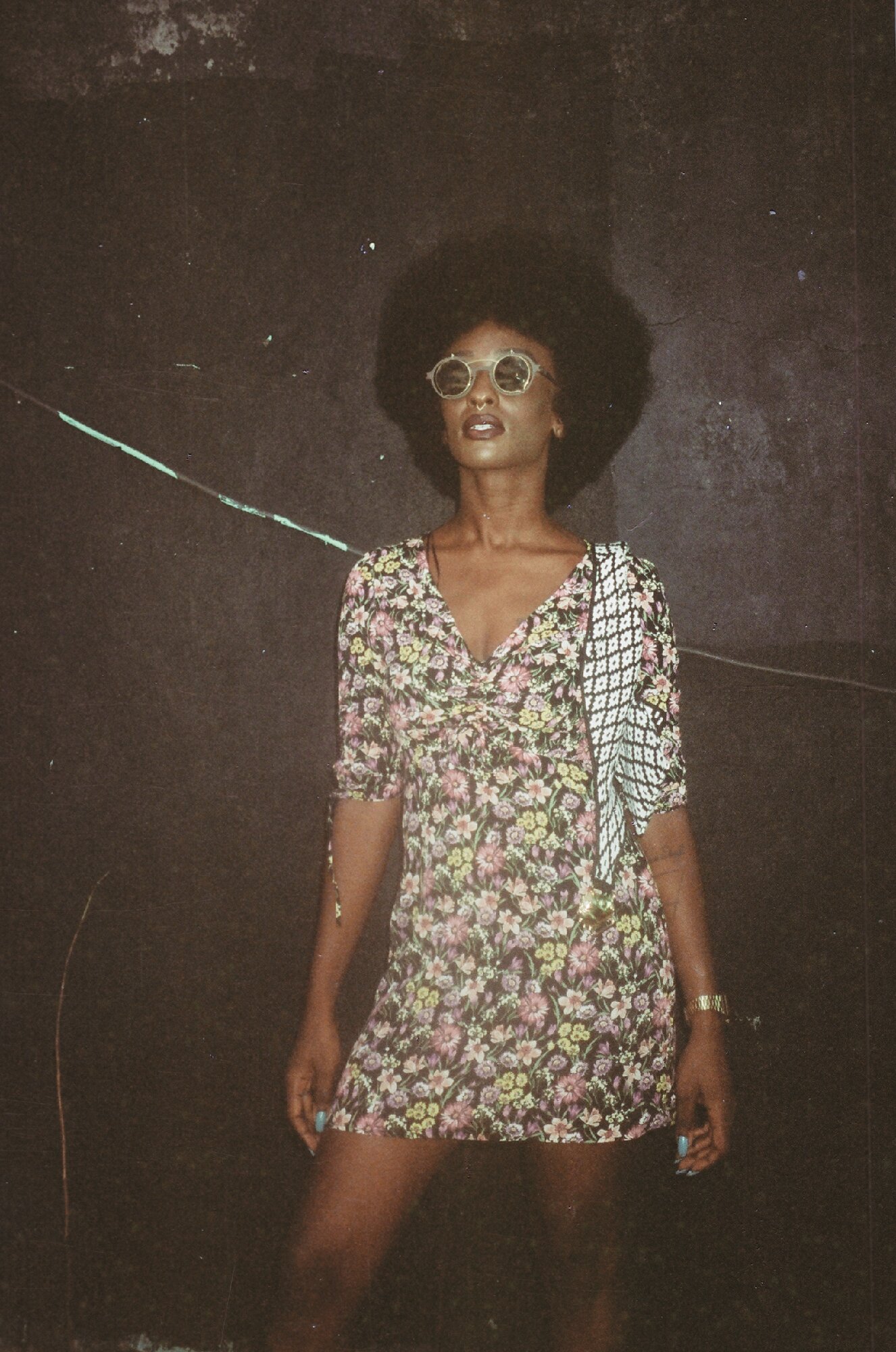

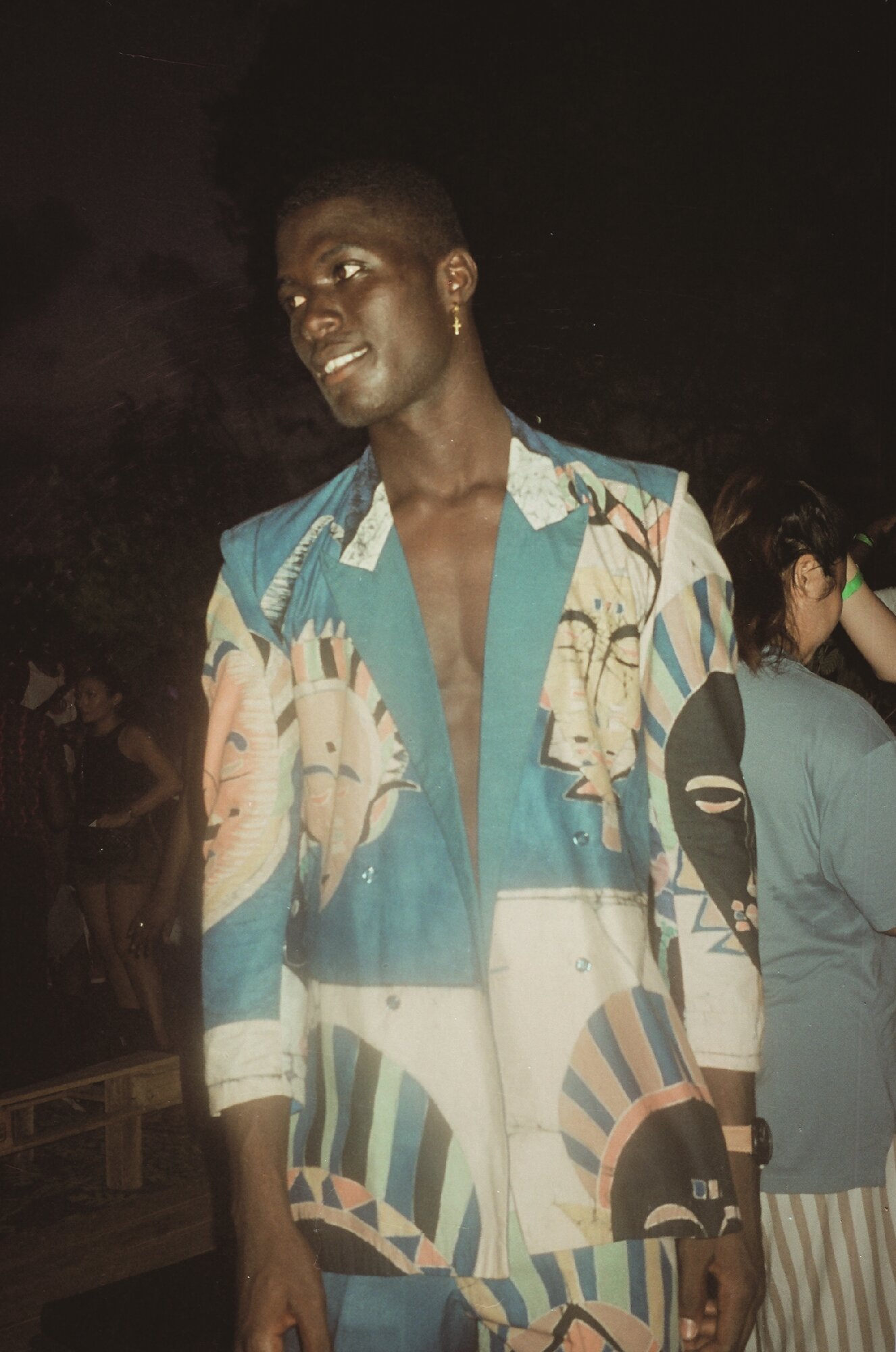

Almost no one in the Ivorian creative scene right now would have missed this new dance, simply called La Sunday. Kader Diaby, the photographer and designer behind the menswear brand Olooh, came wearing one of his own deep V-neck shirts. Fantastyck, a lively Unicef executive who moonlights as an It-girl, danced around, her torso outlined by a lace bodice. The photographer and stylist Louis Philippe de Gagoue came crowned by his signature gilded headpiece. Tony Santanna, who's quietly been making the move from modelling to photography, was there, as were Milc Magazine's Joel Williams and Elle's Lafalaise Dion. Yannick Konan, an international Ivorian model, came dressed in Balenciaga. The Btendance editor, Patrick Edooard, probably the most connected man in Ivorian fashion, discretely observed the scene. Young Nouchi, a vintage fashion expert, licked a yellow ice cream that matched the smiley pin on his Burberry shirt. Dadi, the in-demand photographer known as Nuits Balnéaires, documented the scene for this magazine. The hunky influencer Saint Kacp, who occasionally paints his nails black, checked the door. DJs Asna, Faye, Undee, and Badgalmelv had been invited to perform, as an honour to women.

La Sunday has given the city's indie movement, which had been simmering for a while, a place to call home – and judging from the wild sing-a-long when Sheck Wes’ ‘Mo Bamba’ played, it has found it’s unofficial hymn, too. “People in Abidjan are used to going to nightclubs where people have to pay enormous amounts of money for Champagne. La Sunday is bringing something new,” says Patrick. “People can come dressed as they wish.”

And yet, this game-changing event was founded almost by accident. Late last summer, Jeune Lio, a twenty-something Cameroonian, arrived in Côte d'Ivoire to work in advertising, after studying in Paris and working in Dakar. He barely knew a single soul there, but met Faycal Lazraq, a Frenchman who, after working for nightclubs across the world, settled in Côte d'Ivoire in 2016. One day they thought, ‘Why don't we launch a cool party, just a chill Sunday afternoon reunion with our friends, something like Sunday Groove in Paris?’ They enlisted Black Charles, an Ivorian DJ and marketing exec, Aurore, a former colleague of Faycal at the Yoyo nightclub in Paris and Aziz Doumbia, a pivotal figure among the Abidjan crowd.

By then, Aziz had opened the Dozo concept store in Vallon, which had become a kind of Warholian factory where artists, models and designers flocked to buy pieces by local designers and also to gossip, smoke, drink, eat, or work. The first party took place last December on the pavement nearby the store and the very busy Rue des Jardins. It was to end at 10pm, but the guests partied until 1am.

“I've worked with almost everyone and owe my success to my creative friends”

“We thought it would be great if each of us could bring five or ten friends, but it ended up being 150,” remembers Aurore. Charles and Lionel were anointed resident DJs, offering a mix of soul, makossa, coupé décalé, hip hop and electro. The team also found a mascot, Ahmed, an 18-year-old tea street vendor, who was hired to provide complementary beverages for the Sunday revellers. The following party attracted an even bigger crowd, which overflowed onto the large road, crossed by speeding cars. Faced with an obvious space problem, they shifted the third party to Club House, first on a half tennis court, and then a full court.

The success of La Sunday speaks volumes about Abidjan right now. “The art scene is thriving. We can see that in many sectors, from cinema to circus, to painting and dance, to music and photography,” says Isabelle Zongo, an art critic and founder of the Fondation Original, a digital organisation that promotes African art and culture. "These artists are supported by many private initiatives and embassies, as well as the Ministry of Culture.”

In fashion, brands such as Loza Malhéombo, Yhebe, Olooh and Kente Gentleman are creating a new style. A significant number of them used to be based in Europe or the US, but decided to take the plunge and contribute to their country's development. “When I first arrived around 2012, there were not that many things in the fashion space. Maybe it was just Laurenceairline here,” says Loza. “Winning an Arise Magazine Fashion Week prize encouraged me to move back home. I've since encouraged other people to do the same.”

In a similar vein, Frederique Guei decided to move back from France and together with Francis Yapobi, runs the luxurious concept store Le Comptoir des Artisans. In fact all the La Sunday members have lived abroad at some point, and their work shows the influence of events at Wanderlust or Café Barge in Paris. Also noteworthy is the fact that all members of this community work closely together. “There are a lot of interactions among us,” says Dadi, who recently exhibited at Unseen Amsterdam. “I've worked with almost everyone and owe my success to my creative friends.” Many of these deals are struck at Dozo, where, during my stay in Abidjan, I attended cheerful dinner parties and an emotional talk by art photographer Joana Choumali.

All this is happening at a particular moment in the country's political history. The coalition formed by President Alassane Ouattara and former president Henri Konan Bédié in 2010 has dissolved, fuelling fears for the upcoming 2020 presidential elections. And yet, this new generation of creatives seem to exist in their own orbit. “We don't believe in politicians anymore. We just hope our country won't explode,” says Aziz. “We trust our movement, and what we can create with it. We earn more by doing things on our own. We even get international clients.” Dadi agrees: “There have been actions from the state in favour of culture, but we have the feeling that culture is not strongly supported here. Young people shouldn't wait for the state to do things. This generation has a lot of possibilities, thanks to the internet.”

Other creatives complain about the lack of production facilities and access financing. However when I speak to Hervé N'koumo, director of books and visual arts at the Ministry of Culture, he asserts that there are two funds available, one for cinema and one for arts, which includes fashion. “The thing is, people need to apply with a coherent project, and if their project gets accepted, it may take about six months to get the money,” he says.

La Sunday has faced its own hurdles. At its original location, the rambunctious parties bothered the neighbouring Swell bar, where well-to-do executives like to smoke cigars. The City Hall also sent Aziz a letter saying the noise angered the neighbours. “We arrived like savages,” admits Aziz. “We knew it wouldn't last, but for the tiny amount of time it was possible, we had to do it.” As this article goes to press, the team has just announced that the party is moving to the art gallery Fondation Donwahi. But the organisers remain undeterred, and they now feel ready to travel the party to neighbouring countries.

One of the conundrums of such niche parties is how to widen the influence while keeping it cool. Growing means accepting more people, yet the magic of La Sunday lies in the fact that it’s about a gathering of like-minded friends. “We know we'll have to restrict it. If we don't, we'll lose the vibe,” says Aziz. “It's not about social segregation, it's about having the same mindset. When you want to do a cultural revolution, you need people who follow the same ideology.” By the end of this particular La Sunday in February, a few friends linger with the party organisers as the DJ played some last tunes. "Now I recognise La Sunday,” says Kader with a smile.

This feature was originally published in issue two of Nataal magazine in 2019.

Read our story on how Abidjan’s creative community are coping with the Covid-19 crisis here