Curator Aindrea Emelife discusses how her Somerset House show reclaims the Black female gaze

What began as an early love of museums for Nigerian-British art historian and curator Aindrea Emelife, has since developed into a resume of significance in the art world. While she says she “didn’t grow up in an art-loving family," Emelife's childhood visits to London’s National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery solidified her desire to turn her passion into a practice. “I thought I’d purely be an academic, but what really took me with curation was breaking down themes and immersing people in a story in a visual way,” she recalls. Her ambition to share untold and underrepresented narratives that decolonise African histories has led to her current position as the curator of modern and contemporary art at EMOWAA in Benin City. She’s also going to curate the Nigerian Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia 2024.

This week her globe-trotting exhibition Black Venus opens at Somerset House, bringing together the works of over 20 Black women and non-binary artists. The show examines how Black femininity has been marginalised, fetishised, and reborn through more than 40 contemporary photographic artworks in conversation with archival images originating from between 1793 and 1930.

“At a time when Black women are finally being allowed to claim agency over the way their own image is seen, it is important to track how we have reached this moment,” Emelife asserts. “In looking through these images, which span different stages of history, we are confronted with a mirror of the political and socio-economic understandings of Black women at the time and how the many faces of Black womanhood continue to shift the public consciousness… There’s a spiritual purpose in reclaiming the Black female image for history but also for ourselves.”

Black Venus first went on view last year at New York’s Fotografiska before travelling to MOAD in San Francisco. “Those editions are quite different from this one. What I wanted to do was continue the story and react and respond to the places they’re held,” she says. For the Somerset House iteration, Emilife has added six UK-based artists. “Sentimentally, it's very appropriate to be doing it in London because I was brought up here. A lot of the thinking about the show came from when I was studying [at The Courtauld Institute of Art] and not seeing myself within the textbooks or exhibitions we were given to analyse.” As such, new additions such as Sonya Boyce and Maxine Walker, both prolific artists from the 1980s, make well-appointed appearances as evidence of the enduring presence of Black women artists in the UK, alongside works by young artists such as London-based Jamaican artist Amber Pinkerton.

“There’s a spiritual purpose in reclaiming the Black female image for history but also for ourselves”

An important goal for Emelife was to create a space where young Black women can go to and feel welcome. She references ‘The Origin of the World’, 2022 by Kara Walker, a haunting addition to the exhibition, as a central focus for her outreach. It depicts a Black girl standing in the corner and looking on hopefully for a future redistributions of power. “My mother was very much like, ‘Art isn’t for us; this is for the upper class',” she recalls. This focus on accessibility extends to the ‘pay what you can’ entrance fee, too. Hoping that new and familiar faces will “find joy and encouragement from being in the space,” Emelife endeavours to open doors to the art world, encouraging those who come to embrace a sense of homecoming or celebration.

Through the show’s confrontation of three archetypes – the Hottentot Venus, the Sable Venus and the Jezebel – the viewer is invited to consider how these harmful and oppressive tropes have limited the Black female experience throughout history. By unpacking these ideas, the curation also unveils the qualities that aren’t celebrated enough, such as softness and quietness. “Black womanhood has been so trapped and so narrowly defined in artistry,” Emelife says. However here the gaze turns. “Throughout the installation, I felt a sense pride and of being unapologetically me. That’s how I want visitors to feel too… I’m excited to portray the real expanses of Black women.”

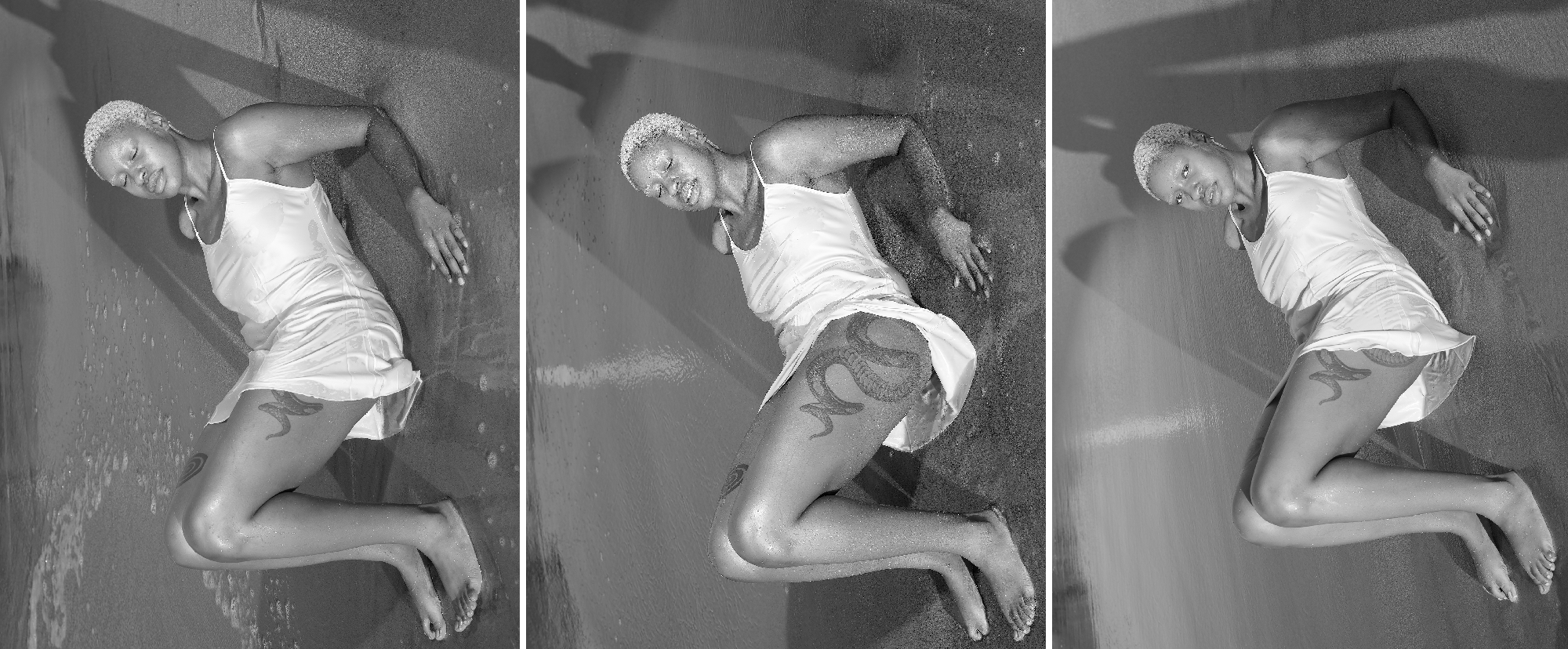

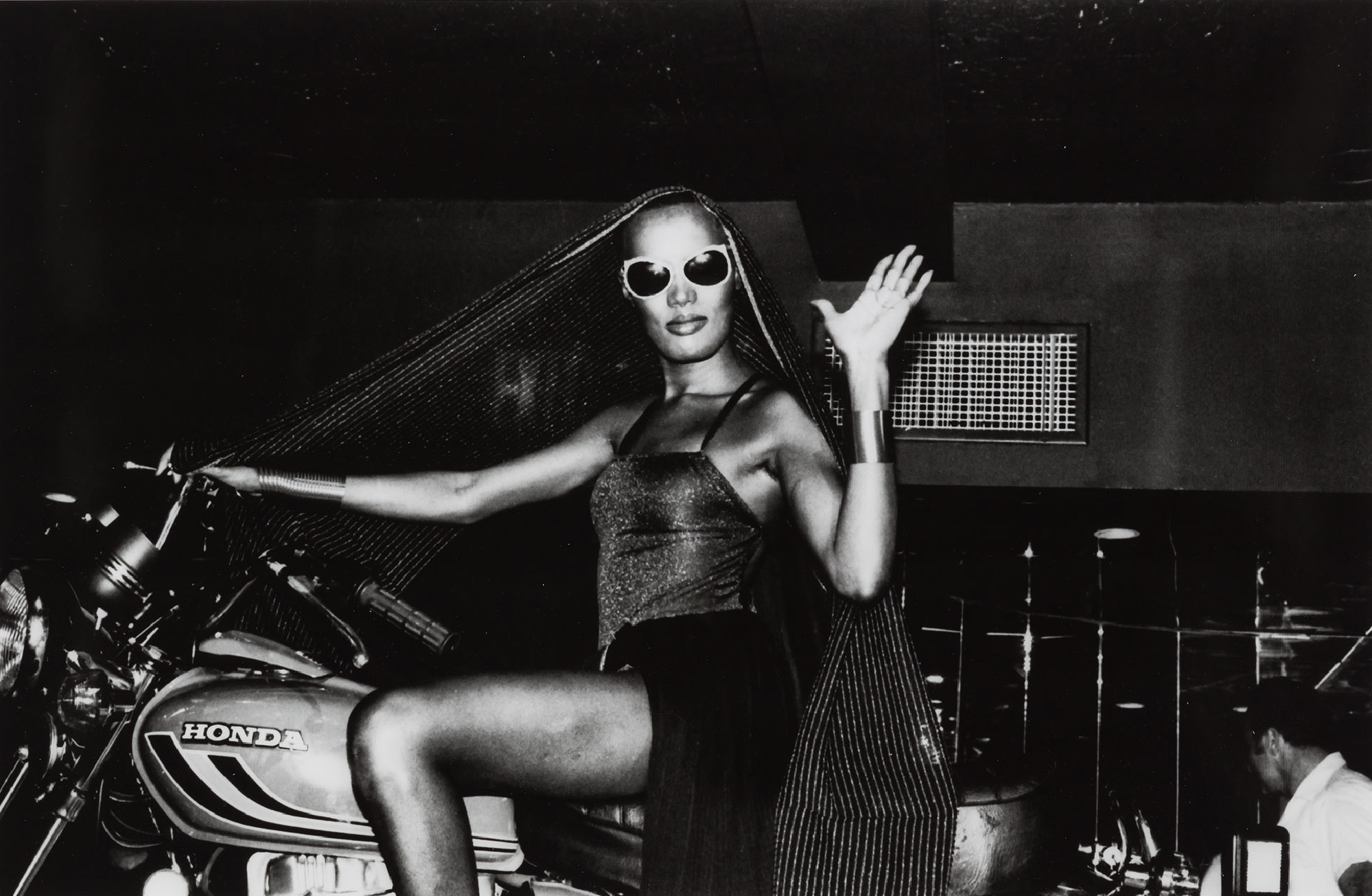

Stand out works include Zanele Muholi’s ‘Miss Lesbian I and II’, 2009, which look at the representation of Black lesbians in South Africa by tearing apart the beauty queen ideal. “Her work is ruffling the very stereotypical portrayals of beauty that are usually seen in art,” Emelife says. Ming Smith’s documentary image, ‘Instant Model’, 1976, zooms in on a woman in the crowd at Coney Island, illustrating that Black beauty is found in the ordinary. And Carrie Mae Weems’ self-portrait ‘When and Where I Enter, the British Museum’, 2007, very much echoes the curator’s ethos for the entire show. She talks about Weems’ practice as “encompassing the subtleness of Black womanhood while inspecting emotionally charged ideas and themes.” And Lorna Simpson’s large-scale ‘Photo Booth’, 2008, an assemblage of archival head shots and ink drawings, is a commentary on the how people’s limited attention to Blackness is predominantly dominated by maleness.

The show highlights how far we’ve come, but also the long road ahead and the work still left to do. “What I would love would be for this to be a catalysing moment for more investigation,” Emelife asserts. “I want other curators and art historians to take on the charge of looking at some of these artists or uncovering more of these stories. I’m really creating a wider bibliography or academic focus on the idea.” It’s this legacy that Emelife hopes to leave behind with Black Venus; a legacy just as inspiring as the show and curator it was born from.

Black Venus is on view until 24 September 2023 at Somerset House, London