With his new exhibition Made

You Look: Dandyism And Black Masculinity, Ekow Eshun explores the disruptive power of wearing it well

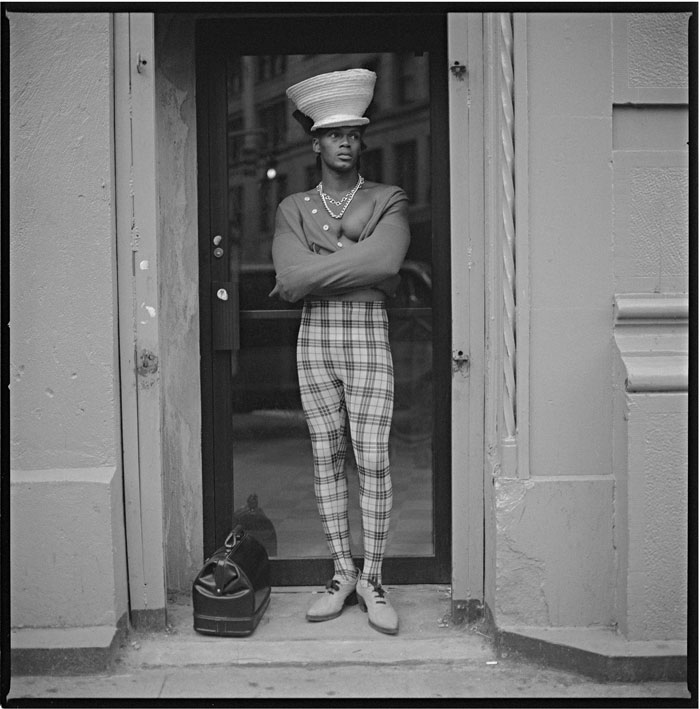

The promotional image for Made You Look: Dandyism And Black Masculinity at London’s The Photographers’ Gallery is of a young man posing nonchalantly in a doorway. He’s wearing super tight tartan leggings, a low V-neck jumper revealing gold chains and firm muscles and a hat high enough to hide a week’s groceries underneath. His is a timeless swag but this moment was actually lensed in New York by Jeffrey Henson-Scales in 1991. “He makes the most fantastically ambiguous and fluid figure,” says exhibition curator Ekow Eshun of this flamboyant gent. “For me black dandies aren’t about this conservative concept of men in suits looking a bit smart. It’s not a superficial thing to do with wearing clothes to impress. It’s a statement of identity against contrary circumstances. It’s less about the clothes than how you wear them, how you hold a physical position in the city that allows you to define yourself in your own terms.”

The incentive for the show, which comprises street and studio photography spanning three continents and more than a century, stems from current debates surrounding black masculinity and dandyism’s ability to counter to the objectification of the black body. “We’re in a moment when black men are both hyper visible and invisible. There’s Barak Obama as president while we’re also among the most vulnerable in society, as the roll call of black men shot, killed or in custody in North America and Britain and the Black Lives Matter moment testifies,” Eshun says. “I’ve always been fascinated by how style carries its own politics and this is a salient point when you’re dealing with black men. Dandies play with those fixed codes of representation dictated by the prejudicial white gaze, and by different black societies, by consciously disrupting expectations.”

Eshun knows a thing or two about putting on a good show. The former director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) is currently chair of the Fourth Plinth Commissioning Group as well as creative director of the Calvert 22 Foundation and contributing editor at Esquire. A regular cultural commentator on TV and radio, his 2007 Orwell Prize-nominated book Black Gold Of The Sun tells of his journey from England to Ghana in search of his ancestry. He’s also currently writing a book on the history of hip hop.

“I’ve always been fascinated by how style

carries its own politics and this is a salient

point when you’re dealing with black men”

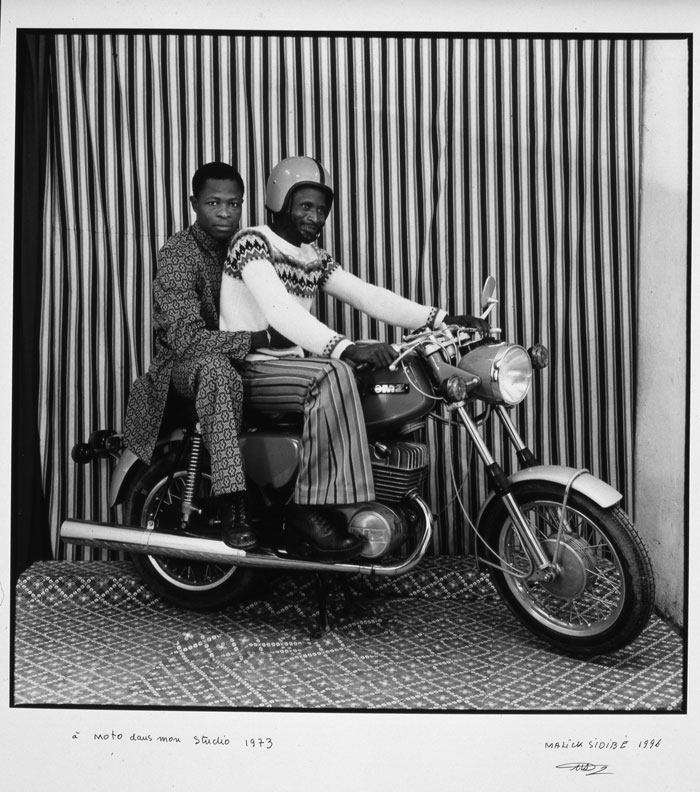

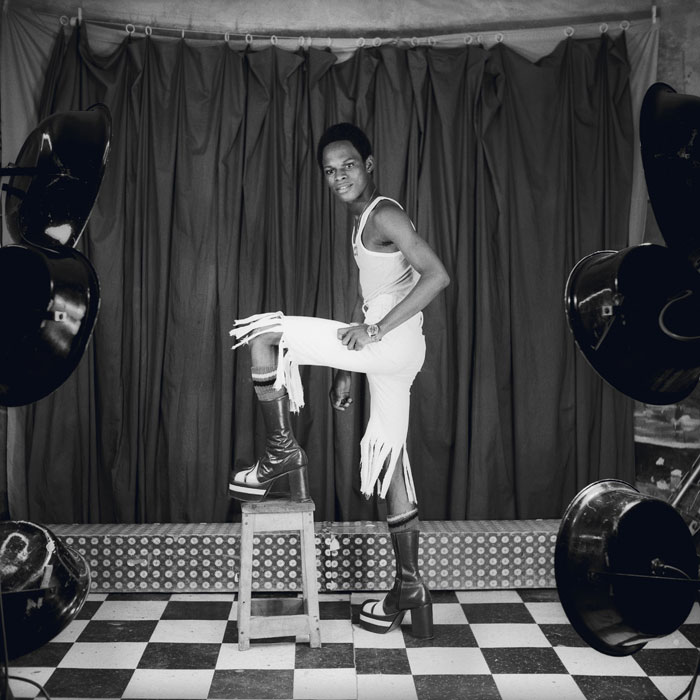

For Made You Look he started off with Malick Sidibé and Samuel Fosso - two photographers he’d long admired. From the former, he was fascinated by how “you can see all of those stresses on deportment and public-ness played out in formal studio photography.” While Fosso’s self-portraits “had a more ironic air and pleasure to them. They were about recognising that we all make our own performance of being men.”

He also selected Liz Johnson-Artur, a photographer he used to commission as editor of Arena magazine in the late 1990s, whose images span 30 years of street life everywhere from Moscow to Kingston. He then went on a journey of discovery to find photographs that further resonated or surprised. The earliest images are by an unknown photographer in the Larry Dunstan Archive depicting a group of Senegalese men proudly posing in all of their finery circa 1904. “There is a knowingness about their elegance, style and extravagance,” Eshun adds. The newest images were also taken in Africa, this time by Nataal contributing photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman whose work creates new mythologies through her cast of opulent, louche characters who reject binary approaches to gender and race in South African today.

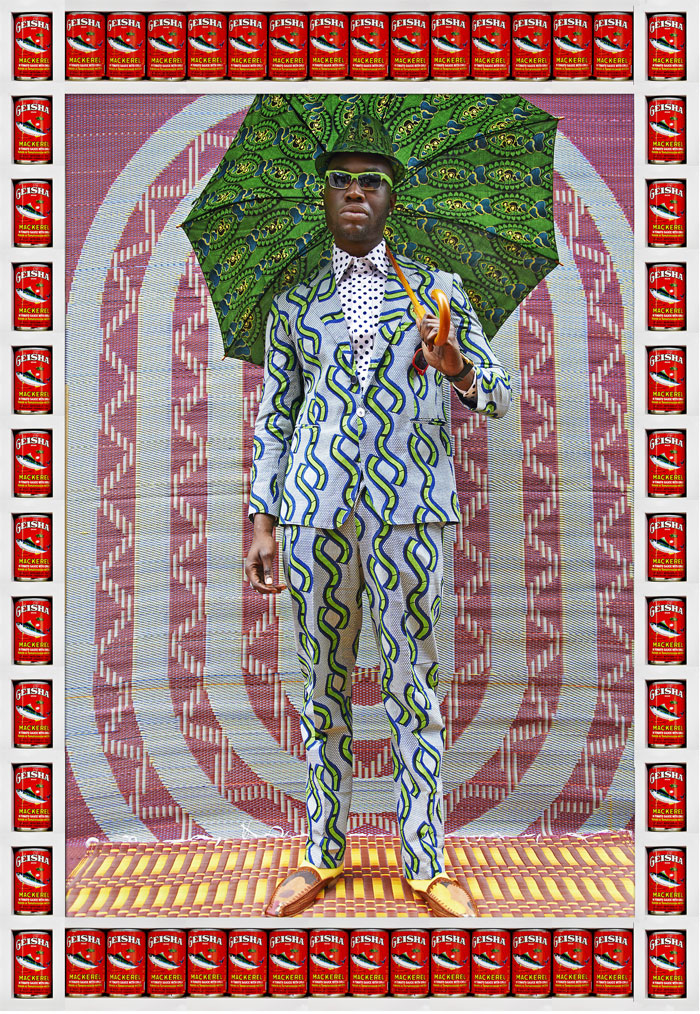

In between these dates, we travel to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s through the imaginings of Isaac Julien’s 1989 film Looking For Langston, and to contemporary London and Marrakech where Hassan Hajjaj styles his friends in designer logos, wax prints and polka dot djellabas. These and other touch points speak to how dandies have long expounded stereotypes with their provocative public displays of fabulousness.

The Oxford dictionary defines dandy as ‘a man unduly concerned with looking stylish and fashionable.’ In 18th century France and England the term was used to describe transgressive aristocrats who elevated peacocking to a spiritual vocation. The lineage can be followed from the musings of Charles Baudelaire to the gallivanting of Beau Brummell to the novels of Oscar Wilde and beyond. Black dandyism however, whether channelled by zoot suiters, swenkas or sapeurs, historically started from a polar position.

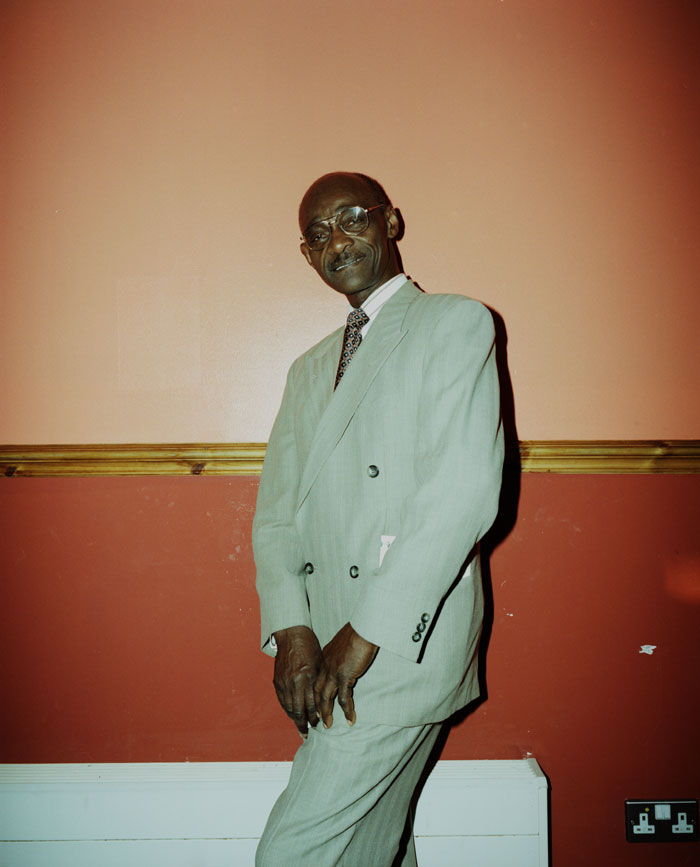

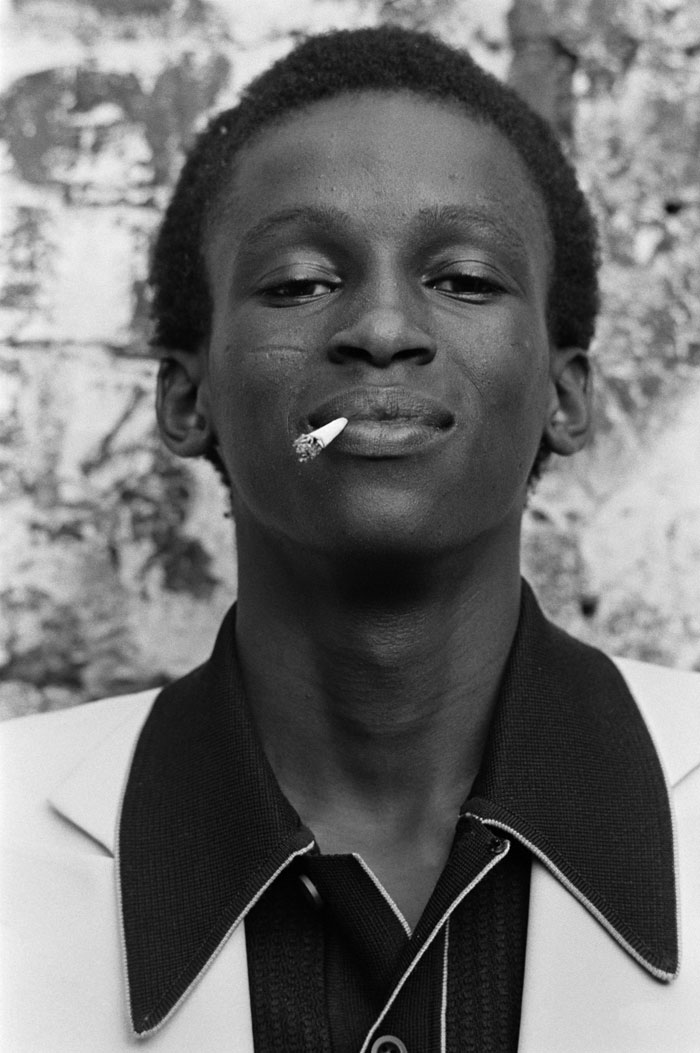

“Famous dandies such as Lord Byron could get away with dressing or behaving outrageously because they already had status. A black dandy though had no inherited power so it took bravery to define themselves in those terms.” Eshun cites a work in the show, Colin Jones’The Black House (1973-1976), which was shot in a hostel on Holloway Road, north London. “These were portraits of disaffected black youth. None of them had money or status and yet they wore their tatty clothes so well that they look lordly. It’s as if nothing had ever been denied them. Through their dress and manner they claimed an inheritance they had been precluded from. This for me sums up how dandyism can be a way to assert yourself, to use how you look as a conduit for your pride and power.”

Made You Look is part of a growing artistic discussion surrounding dandyism, as exemplified by recent exhibitions Return of the Rudeboy at London’s Somerset House and Dandy Lion at the Museum of African Diaspora in San Francisco as well as Ariel Wizman’s Black Dandy documentary. In our increasingly visual culture, where does Eshun see the influence of the black dandy going next? “There’s this sense of a shifting culture. Creativity is really opening up conversations around identity and having an impact of society at large. We’re moving to a place where the true heroes are those people who claim the right to be themselves. I grew up listening to Prince’s artistic possibilities. Hopefully that hybrid otherness will become commonplace rather than an extraordinary thing.”

Made You Look: Dandyism And Black Masculinity is at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 25 September 2016

Words Helen Jennings

Visit The Photographers’ Gallery