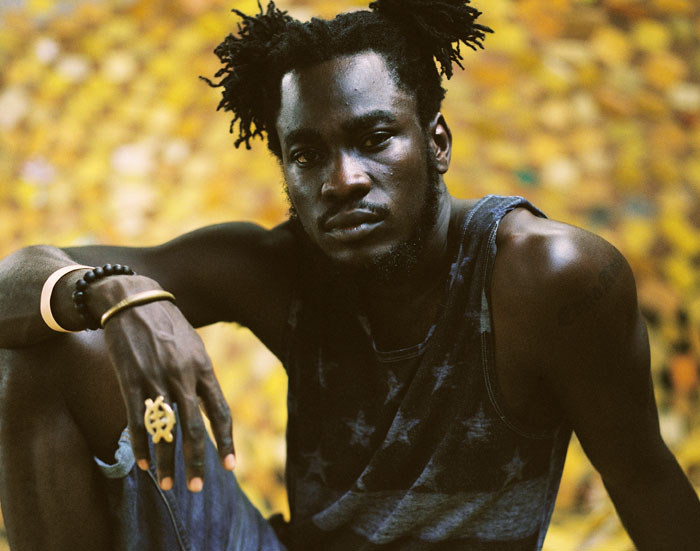

The mixed media artist invites Nataal into his Accra studio to discuss his socially engaged concept of Afrogallonism

“He is one of the most talented people I have come across in my life,” says Marwan Zakhem, founder of Gallery 1957 of Serge Attukwei Clottey. “He has an incredible presence and has the ability to work across all types of mediums, be it painting, photography, sculptures or performance.” Zakhem has been so taken with the artist’s output that he opened his Accra art space in March 2016 with an exhibition of his body of work, My Mother’s Wardrobe, and then went on to dedicate the gallery’s booth at London’s 1:54 art fair in October to his solo offering too. “Serge’s work is closely tied to issues of politics and culture in Ghana, and has been integral to promoting the contemporary art scene both within, and outside of, the country.”

This is high but well-deserved praise for Clottey, whose star has been rising steadily for the past decade. Dedicating himself to addressing national and African issues around social injustice, trade, migration and post colonialism - as well as deeply personal family concerns - he's become known for experimenting with everyday and discarded goods, such as rubber tyres, buckets, jute sacks, wires and wood. His biggest inspiration though are yellow plastic Kufuor gallons. These are a ubiquitous sight in Ghana having originally been imported from Europe containing oil, and then endlessly recycled to carry water by those struggling with the country’s water shortages. His creative reinvention of these jerry cans, through cutting, stitching, melting, stacking and wearing them, has developed into a concept he calls Afrogallonism.

“I began exploring them after realising how much time I have spent working with plastics. It is such a loaded symbol in Africa, bringing up environment issues, while also considering the impact of consumerism in the African landscape,” says Clottey. “The opportunities to use gallon containers are endless, there are elements of masquerade, and a versatility in their materiality. Afrogallonism is the new Africa, the future of Africa.”

The vivid results, whether a new take on an African mask or a large-scale installation, change the value and meaning of his source materials. Simultaneously familiar yet strange, his works solicit an innate response from his local audience. “By considering the value of the everyday objects we are surrounded by, we are engaging in the nature of consumerism. Using materials that are commonly in circulation in the area also means that there is a relevance to an audience who may not be interested in art, which in turn will hopefully encourage creativity in younger generations.”

Born and raised in the Labadi area of Accra, his father was an artist and encouraged him to follow in his path by enrolling him in Ghanatta College of Art. “I grew up surrounded with art. Before I started college we would study my father's paintings together, and I would draw a great deal. At the time, I wasn’t sure whether art was just a hobby or actually a career. My studies in Ghana and a scholarship in Brazil really motivated me to become part of the contemporary art scene, enabling me to think about different approaches to my work and what it was that I wanted to communicate artistically.”

"I comment on society and politics, and doing so in a public space means that it has an immediate impact on the people around me, who might not otherwise see my work in a gallery"

His non-traditional approach did not at first find favour at home but increasing interest from abroad, leading to recent exhibitions in London, New York, Hamburg and Beijing, has helped spread his message. And in Ghana he’s found his most powerful form of agency through his performance collective GoLokal. “Performing in the local community means that we have a way of critiquing things in a safe way. I like to comment on society and politics, and doing so in a public space means that it has an immediate impact on the people around me, who might not otherwise see my work in a gallery. It creates a dialogue and offers an alternative narrative to the ones politicians would like us to hear. This isn’t just something I am doing for myself, I am doing it for the entire country.”

During the 2012 Ghanaian elections, his GoLokal ensemble dressed up like wealthy politicians in suits while dragging Clottey through the streets by a noose with a sign saying ‘Youth’ around his neck. The event was widely covered by the local press. Meanwhile as part of My Mother’s Wardrobe at the inauguration of Gallery 1957, which this year has become a valued and refreshing addition to the city’s art scene, he and other male performers led a procession wearing their deceased mothers’ clothing. In the Ga tribe tradition, when a mother dies, her possessions and fabrics are locked away for a year and then given to female family members. As the only child and only son, Clottey felt a loss of connection and also wanted to make a comment on gender roles. “Textiles and materials in Ghana, and other parts of West Africa — each weft, line or mark — are potent carriers of memory, of communication, and the artist weaves into his sculptures subtle traces of loss, remembering, and of rebirth,” says Nana Oforiatta Ayim, who curated his Gallery 1957 show.

Thanks to Gallery 1957, and other major players such as the Nubuke Foundation, Accra [dot] Alt and KNUST, Accra is becoming a healthy breeding ground for artists who embrace emotive and experimental practices. The scene unites for the city’s annual Chale Wote Street Art Festival, which this August is where Clottey curated his most recent performance, entitled Practical Common Sense. “It was a call for recollection and re-contextualisation of indigenous beliefs and practices. The performance looked at how traditions can be practiced in contemporary society and asked, ‘Should they be discarded or preserved?’ The success of Chale Wote says a lot about the demand for performances of this type. This year was the 5th edition of the festival that brings together music, art, performance and dance. It is an incredible opportunity for all artists of all ages to converge and work together in an immensely public way.”

As Clottey reflects on what has been perhaps his busiest year yet, the artist looks forward to getting back into the studio and reinvigorating his practice with new residencies in 2017. His next project is River Goddess. “It will be a large installation built of stitched plastics that will cover the Kpeshie Lagoon,” Clottey says. “It was once an incredibly valuable source of fishing and food, but due to recent commercial and industrial redevelopments in the city, it has become a polluted dumping ground. In Ga culture, bodies of water are protected by sea gods, so I hope to examine how our neglect has altered our relationship with the gods who have served us for so long.”

Words Helen Jennings

Photography Rudi Geyser

Visit Serge Attukwei Clottey

Visit Gallery 1957