Reflections on the purpose and achievements of the inaugural Stellenbosch Triennale

Stellenbosch is a complicated space for an event focused on African art. In some ways, it is perfect. With idyllic winelands and a strong culture of artisans, it lines up well with the artistic imagination. But as the Cape Province’s second European town, founded in 1679, it is also a complex social and historical location. Just 30 years ago, almost none of the esteemed artists from every corner of Africa would not have been welcome in the city; let alone in its most prestigious venues. Even today, socio-political issues of race, labour division, and the violence of its founding remain pervasive in terms of how people interact, where different groups live, and the extreme inequality which is a key feature of South African society.

But this is also 2020: a time when African art, through decades of challenge and conflict, can find a real home in South Africa, and where the charge can be led by African people. And as the theme for the inaugural Stellenbosch Triennale encapsulates, the charge is clear: “Tomorrow there will be more of us…”

“African artists are proposing radically new ways of making, looking and experiencing the world”

The Stellenbosch Triennale is the brainchild of the Stellenbosch Outdoor Sculpture Trust, who has a long history of public art events in the area. Despite being the country cousin of big city Cape Town, Stellenbosch and its hoard of students have a voracious appetite for fine art. On a stroll to The Pulp Cinema, I passed no fewer than 10 galleries, some grand and sprawling, others small and discrete. But street-side galleries were not the limit of Stellenbosch’s art potential; and so the Trust, along with its team of curators, thinkers and planners, had to go further. It had to deliver the beating heart of African artistic creativity, and display it with pride across the town. And so the Stellenbosch Triennale was born as a monument to contemporary African art.

As one of its key curators Bernard Akoi-Jackson, explains: “The Triennale offers us all a great opportunity to come into contact with new work that is exciting and challenging in equal measure. The kind of artistic practices that are emerging from the continent question received notions of art in many ways. Contemporary African art is challenging knowledge of media. Artists are introducing novel methodologies and questioning notions of linear history. New art from Africa is confronting intersectionality and gender stereotypes… But it's all so fun too, because the artists and their art engage with play and present a safe atmosphere for people, both young and old, to imagine life anew and to dream again. Contemporary African artists are proposing radically new ways of making, looking and experiencing the world.”

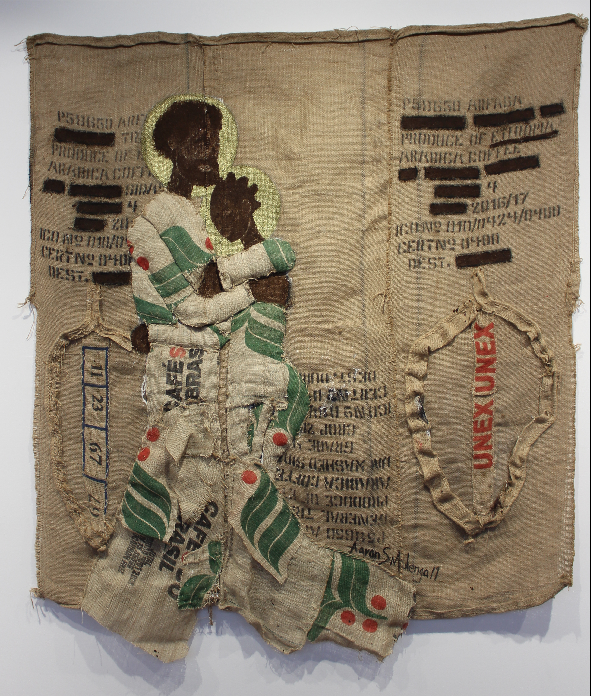

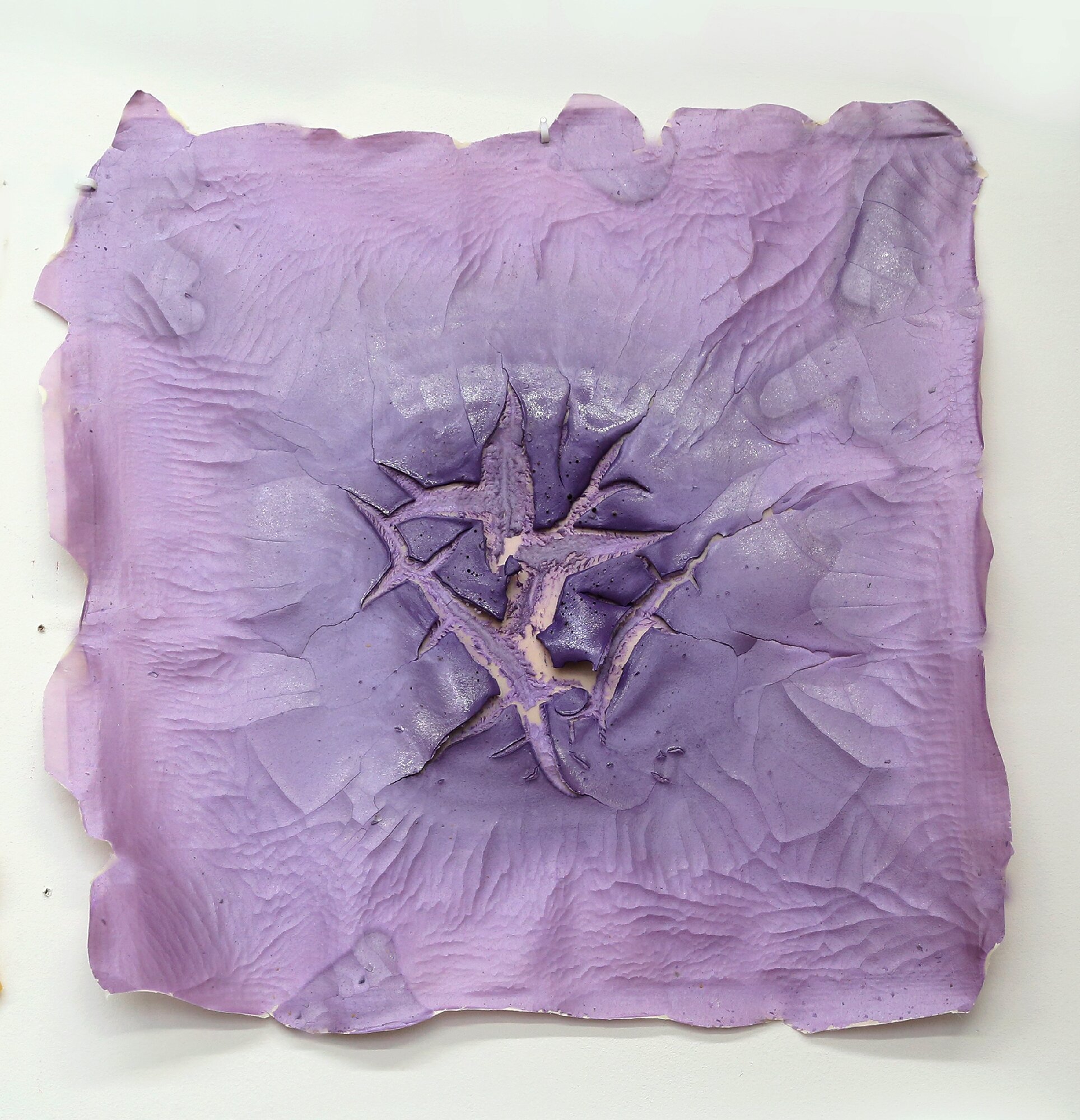

The Triennale played host to many established artists in the Curator’s Exhibition including South African Bronwyn Katz, Congolese Patrick Bongoy and Nigeria’s Victor Ehikhamenor. Meanwhile the On The Cusp exhibition placed its sole focus on “revealing and unraveling the creative talents of tomorrow”. Particularly exciting was Ugandan artist Canon Rumanzi, who blended together photography, photomanipulation and graphic design into collage-like pieces. In the Concepts of Freedom video installation, Malibongwe Tyilo drew on his own heritage to create a narrative that can be retained as part of his familial and artistic legacies. And among my favourite works were by Sungi Mlengeya and fellow Rhodes University alumnus Aaron Samuel Mulenga.

The exploratory curation style extended not only to the choice of artists, but also to the way the Triennale space itself was organised. While an 18 century Dutch-style home is not my first choice of venue usually, its spacious rooms with wooden floors and creaky ceilings, were perfectly atmospheric for staging films. From venues, to the choice of artists, to the space in which their work lived, everything about the Triennale felt deliberate. Dr Tigere Mavura, adjunct curator and Stellenbosch Outdoor Sculpture trustee, describes the Triennale as a “good creative platter for everyone”.

However, the project was not without its hurdles. While the ambition of a town-wide Triennale allowed for long walks to peek into different exhibitions and the chance to bump into its artists, some elements were delayed, causing confusion at points. That is perhaps natural for a first go around of an event of this scale. Ultimately, the curation was clear, and in the spirit of growing African art and community, the Triennale provided opportunities for artists from all over the continent to connect, discuss and share their practices with one another. Its success for me, lay in its celebration of itself, its artists and the vision, rather than being positioned as a glitchless stage production, intended to dazzle and wow – as is the trend of many large-scale art events around the world.

While not on the official programme, the opening event’s rap performance piece let attendees know they were in for something special. It brought together a collective of local poets and musicians to chronicle the history of Stellenbosch with honest, unashamed criticism. These artists acknowledged the story of the land on which they stood, the fight of their ancestors and their hope for the future. Like the Triennale itself, it was deeply thought through, visionary and remarkably unpretentious.

Read our Stellenbosch Triennale interview with Patrick Bongoy here.

The Stellenbosch Triennale is temporarily closed in line with the nationwide lockdown for Covid-19 prevention. Details about its reopening will be available here.