Discovering Khanyisile Mbongwa’s stirring curation of Liverpool Biennial 2023

“In my mother tongue, ‘uMoya’ means breath, air, spirit, wind, soul. It was important for me to have this intimacy in the language that specifically carries people who have been colonised, enslaved, displaced and disassociated from their native tongue,” says Khanyisile Mbongwa of her theme for Liverpool Biennial 2023. “The word is a way to account, to keep record, and to make the English language more agile so that it can do the softer things we require it to do for the work we’re doing here. That work is to hold a line between catastrophe and aliveness.”

“These are artists whose thematic practices imagine themselves into aliveness”

‘uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things’ specifically addresses Liverpool’s colonial history as a city built on the transatlantic slave trade, and is a rallying call for ancestral and indigenous forms of knowledge, wisdom and healing. The South African artist, previously the chief curator of the 2020 Stellenbosch Triennale, defines her curatorial practice as one wedded to “Curing & Care”. Here she has brought together 35 artists from six continents whose works become portals for recognising woundedness and enacting a reckoning. “These are artists’ whose thematic practices, as Black people, Brown people, queer people, imagine themselves into aliveness. We are moving through historic and contemporary spaces of duress so how do we move through all of this for a healing to happen?”

Now in its 25th year, Liverpool Biennial is the largest free festival of contemporary visual arts in the UK, and takes shape across the city centre from major institutions to derelict buildings and outdoor interventions. This year’s line-up including Lubaina Himid, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum and Belinda Kazeem-Kaminski, embraces the winds that moved merchant ships full of bodies in and out of its docks, and now can be harnessed in and around those same docks, to manifest power and agency for those summon it.

Mbongwa has paired each venue with a “grounding artist” who exhibits a vision that is able to embrace visitors and other surrounding artworks alike. In doing so, we are invited to fully encounter the exhibits. “The work requires us to open up a bit, travel within ourselves and search our internal being, so it was important for me to create moments in each venue where you are held by the work,” Mbongwa explains. “When we’re thinking about the trade of people, of good, of ideas, these moments allow you to contemplate your own positionality and possibly not see yourself as an audience but as a witness.”

The anchoring work at Tate Liverpool, and an excellent starting point for your encounter with the biennial, is Torkwase Dyson’s ‘Liquid a Place’ (2021). These three monumental structures by the US artist are reminiscent of ships and passageways. Impressive and imposing at the same time, their pleasing curves and angles lure you into the depths. Meanwhile at the Tobacco Warehouse, a live offering by Albert Ibokwe Khoza, ‘The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu’ (2022), centres the venue. The South African artist’s performative installation is a visceral response to the traditions of human exhibitions in Europe dating back to the 1870s as well as a ritual giving lost souls safe passage back home. Of this and other performance works, Mbongwa says: “It was an important focus for me to work with artists who centralise their bodies as site of interrogation in relation to the histories that their bodies carry. When we open the door of no return, what does that look like?”

A more whimsical and fantastical moment comes from Rahima Gambo at Open Eye Gallery. The Nigerian artist presents ‘Nest-works and Wander-lines’ (2021) and ‘Instruments of Air’ (2021) which delve into her use of walking as part of her practice, her meanderings through Laongo, Burkina Faso, captured as a delicate video and object installation. She moves with the breeze, discovering herself and her surroundings through a multisensory experience. “I have always been interested in how the body knows before the mind knows, remembers and recognises without visual prompts, and communicates beyond standardised language,” Gambo says. “The intent of these works was to make a return and recovery, works that would put air back into space, return to me a language that was embedded and lost in my body, re-configure me back together and put me back right with land and lineage.” By contributing these pieces to Mbongwa's curation, Gambo speaks to its ability to mend. “A biennial can be medicine, it can be a balm. A biennial can take us on a journey and return us with much more than we departed with.”

Similarly soothing are the works of Ranti Bam at Our Lady and St Nicholas Church Gardens, which in 1717 became the resting place of Abell, Liverpool’s first recorded Black resident and former slave. The British Nigerian artist presents her ‘Ifa’ series (2021-23). The title references the Yoruba I-fàá, meaning ‘draw close’, as well as Ifá, the Yoruba system of divination. Within the grounds stand a circle of wooden stools upon which seven large, perfectly imperfect clay vessels sit. Semi sagged, their cracks, creases and seams all on show, they become totems begging to be hugged.

“My work is about fragility, vulnerability and care, which fits into the biennial’s preoccupation with how we care for bodies in this world, how we live together,” Bam explains. “We are living in an increasingly politicised time, when the distinction between ‘us’ and ‘the other’ is ever more pronounced. I believe that the relationship we have with others starts with the relationship we have with ourselves. So, this work is my relationship with my body and this body in the world.” Significantly this is the first time Bam’s works have been exhibited outdoors, at the mercy of the nature and mankind. “They are fragile and they speak to this semiotics of the feminine. You are welcome to touch them. Anything might happen to them, it’s all welcome. And whatever does happen says everything about who we are as a society.”

“A biennial can be medicine, it can be a balm. It can take us on a journey and return us with much more than we departed with”

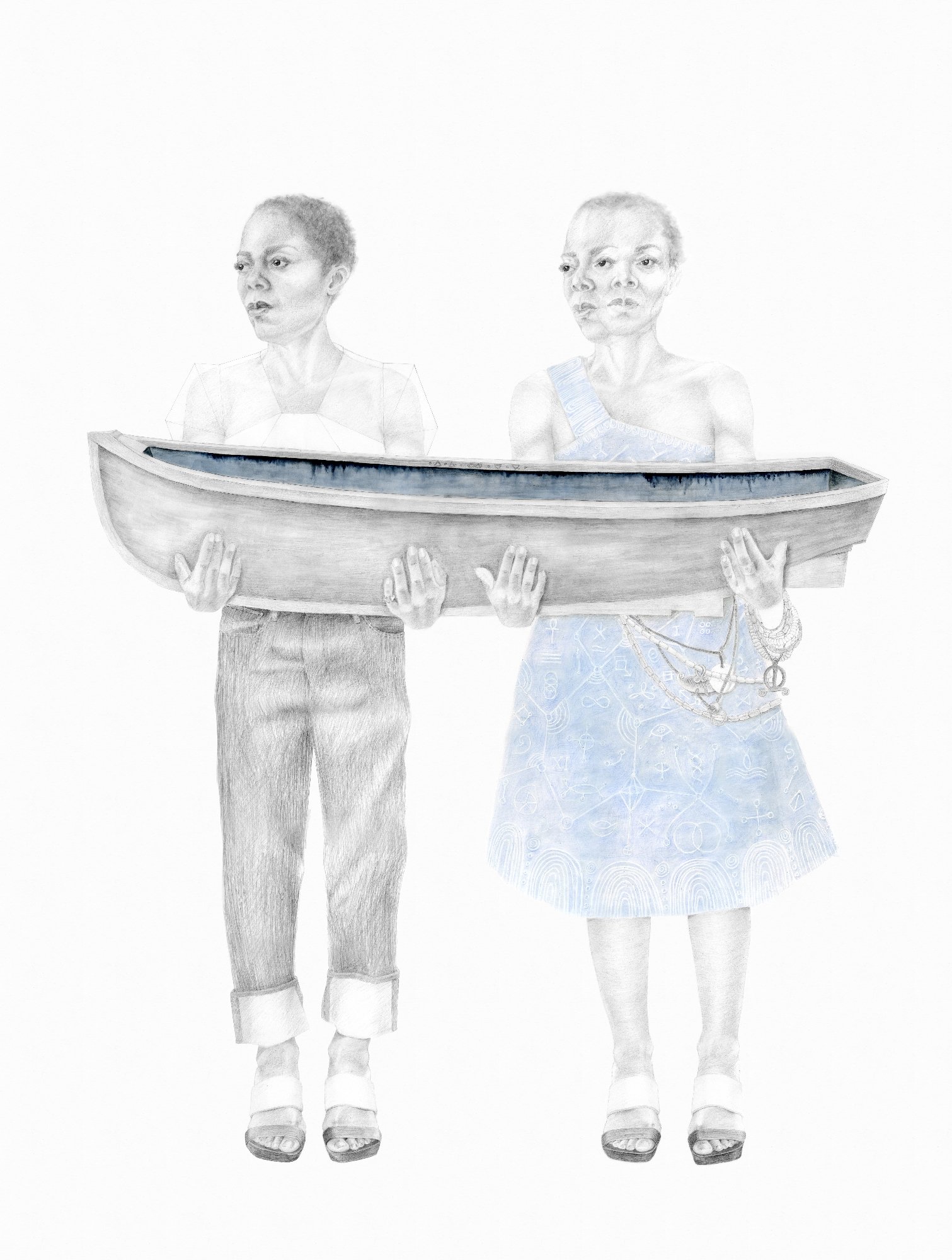

Another standout contribution comes from Charmaine Watkiss at Victoria Gallery & Museum. Responding to her 2018 pencil on paper drawing ‘The Return’, the British Jamaican artist has created ‘Witness’, two more mixed media drawings and her first ever sculpture that continue her “memory stories” of African ancestral knowledge that survived the Middle Passage to shape Caribbean culture. The original work looks at the history of indigo as a sought after and mystical pigment. “Indigo was produced on the plantations where so many people were not afforded a proper burial. It also has very spiritual connections. So, I wanted to make new works that acted as memorial,” Watkiss says.

One drawing summons up the water goddess Mami Wata, the other hails Nanny of the Maroons, who is a heroine of the Akan people for defeating British troops. Between them sits a clay, brass and copper bust surrounded by tobacco pipes and aquamarine crystals, which turns the gallery into a healing zone. “The works speak in a quiet way about liberation. The children of the diaspora have been seeking liberation since day one. I wanted to remind people of the strength and dignity of my predecessors. Without them, I wouldn’t be here today,” Watkiss adds.

On view throughout the summer, ‘uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things’ is a provocative, mediative and uplifting gift to Liverpool. At once vital and joyful, Mbongwa hopes its legacy will remain after the art has long departed. “There will be a residue that is felt over time. Memory is fickle, so I can’t control how people will feel, but what I find fascinating is that the shift happens years later. The relationship with a space influences the choreography of a city. It’s another way to dance with and listen to a city. So, the energy we’ve created here will live on in the air, water, light, and our bodies.”

Liverpool Biennial happens at venues across Liverpool until 17 September 2023